Autism

The Man in the Moon: Faces and Autism

A new method for spotting and understanding autism

Posted November 23, 2016

I love it when a plan doesn’t come together.

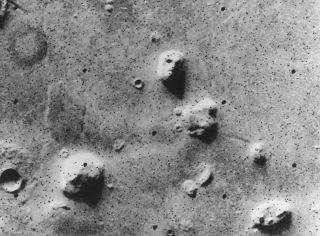

In this case, I was planning to use pareidolia to see if humans around the globe saw the same sort of expressions and faces in things that, strictly speaking, don’t have faces.

If I’d mentioned “pareidolia” ten years ago I would have received a chorus of “huh?” But the internet has changed all that. In amongst the kittens, the politics, and the sunsets-accompanied-by-improving statements, we now all open our social media feeds to be greeted with washing machines that appear to be vomiting clothes.

To anyone who doesn’t open social media daily, pareidolia is the phenomenon whereby humans are predisposed to see faces in objects—sometimes collections of objects—that actually don’t have faces. There is fierce technical debate in neuroscience as to whether there is a specialised area of the brain (the fusiform gyrus) that is particularly adapted to spot faces. As a service to any non-neuroscientist who has wondered in by mistake, I shall summarise this highly technical debate as follows;

“If there isn’t an area of the brain that is specialized to see faces then it is true to say that there exists an area of the brain that will do until a more specialised area is found.”

And that’s as much as I’m going to be drawn on that.

The How and the Why

Whatever the proximate (nuts and bolts) mechanisms for face-recognition (“how?”), the ultimate causes (why the ability improves fitness) aren’t hard to find.

For hyper-smart (no, seriously, we are, even when it doesn’t show) and hyper-social beings like ourselves the face advertises many things in the marketplace. Health. Mood. Alliances. Danger. Opportunity. Faces are signallers. The pioneering work of Paul Ekman (which you might have seen showcased in the excellent Inside Out) identified six basic emotions (that some now expand to seven). These emotions—surprise, joy, fear, anger, disgust, and sadness (with the possible addition of contempt) capture the basic ways in which an organism can respond to stimuli--and provoke responses in others:

Surprise? Watch and see what happens. Joy? Embrace the opportunity. Anger? Attack or otherwise repel it. Disgust? Get it out of you or your presence. Sadness? What cannot be cured, must be endured. Finally: Contempt—get it away from me, it is beneath me (seeing and hearing a lot of that one around at the moment for some reason).

We can spot these responses instantly in one another and from a good distance. It’s probably useful to be able to recognise anger in a face attached to an arm holding a throwable spear, for example….

Faces and Autism

Back to my plan. And its demise. A student came in to see me. She liked the use of pareidolia but she wanted to use it to study autism. Now, autism isn’t really my field, and any scientist is wary of venturing outside their expertise. However, she was confident that we could bring in a proper expert for the technical bits to do with autism and she was obviously willing to put in the necessary legwork herself too. OK. Now what?

It’s reasonably well known that people on the autistic spectrum (now known as Autistic Spectrum Disorder—ASD) have a tough time recognising intentions in others. This leaves them in a tricky situation, socially.

Faces are not quite the same thing as intentions, but there is a pretty strong covariance between things that have faces and things that are ascribed to intentions in our world. For instance, it’s pretty unusual to ascribe pain to creatures without faces. And in the anonymous world of the inter-webs and texting what have we done to add this dimension?

Can’t guess?

As an aside, it’s interesting to discover that religious folk are more likely to ascribe feelings and intentions to objects than non-religious folk are, as this recent Helsinki study made clear (1). In fact, there are plenty of scholars who think that the whole religion thing got off the ground because, basically, we were trying to communicate with the weather (2).

That’s all very interesting, but where does it leave us? We got interested to know if pareidolia would make a test of autism and, as luck would have it (via our newly recruited expert), we had access to a reasonably large (n = 60), representative, clinical population in a public health disability service here in Ireland. After getting all the proper ethical permissions from IRBs, parents, and Guardians we presented ASD folk, and a baseline for comparison (Traditionally developing or “TD” folk) with a series of objects, real faces, and objects that might be interpreted as faces.

They were asked to respond as fast as possible when they saw something like a face, and we also recorded false alarms to weed out anyone who just bashed every button as fast as possible, or clicked on nonexistent possibilities.

Both ASD and TD groups did pretty well (80 percent detection rate). But the pattern of responses was the interesting bit. Both groups got better as time went on (as you would expect), but the autistic kids always trailed behind the TD ones.

So What?

What this all suggests is that ASD kids are less spontaneous in their recognition of face-like objects in their world. They can learn it, in fact, they can get quite good at it, but faces just are not as relevant (or as neuroscientists say, salient ) for them as they are for other people (3).

Why does this matter? Being more oriented toward things than people may be, as Simon Baron-Cohen is fond of saying, less of a disability than it is simply “another way of being human” (4). That said—there are disabilities associated with being ASD in this highly social world. But the good news is that we can teach people to be better. A learned skill may not be quite the same as a natural talent—but it will certainly help. And we have here a proof of concept for a diagnostic tool for identifying ASD relatively early in life, in a test that is easy to administer, and fun to do. We’d like to develop it into a full-blown clinical tool--anyone interested in this is welcome to get in touch.

(Oh, and many thanks to my student and coauthor(s) for having a better plan than mine).

References

1) Lindeman, M., Svedholm-Häkkinen, A. M., & Lipsanen, J. (2015). Ontological confusions but not mentalizing abilities predict religious belief, paranormal belief, and belief in supernatural purpose. Cognition, 134, 63-76.

2) Johnson, D. D. (2009). The error of God: Error management theory, religion, and the evolution of cooperation. In Games, groups, and the global good (pp. 169-180). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

3) Ryan, C., Stafford, M. & King, R.J. (2016) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46: 3838. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-2927-x

http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10803-016-2927-x?wt_mc=Intern…

4) Baron-Cohen, S. (2000). Theory of mind and autism: A fifteen year review.