Sex

Rapture of Distress: Freudian Psychoanalysis Meets the Laws of Manu

How Indian women's sexuality adapts to contemporary patriarchal society.

Updated November 27, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- Freud was not thinking about South Asian or Indian women; his purview included primarily Western women.

- Today, Indian psychoanalysts continue to use Freud’s ideas to undertake novel research in diverse settings.

- A new book argues that the absence of a sexual revolution means that India had different priorities.

- Indian women subvert the patriarchal system by finding risky and creative ways to pursue their desires.

Sigmund Freud once said to Princess Marie Bonaparte, one of his great admirers, whose wealth popularized psychoanalysis and helped Freud escape Nazi Germany: "The great question that has never been answered, and which I have not yet been able to answer, despite my thirty years of research into the feminine soul, is 'What does a woman want?'” Of course, Freud was not thinking about South Asian or Indian women with all their intersectional complexities of caste, class, region, and religion (Hindu, Muslim, Sikh, Christian, Parsi, or Dalit); his purview included primarily Western women, who were suffering from maladies of the soul, invariably related to what Freud described as blockages in their psychosexual development.

Marie Bonaparte was the great-grandniece of Emperor I of France, who suffered from frigidity and an inability to reach orgasm. She undertook arduous research and became a practicing psychoanalyst and spearheaded the early dissemination of Freud’s ideas in Europe and America.

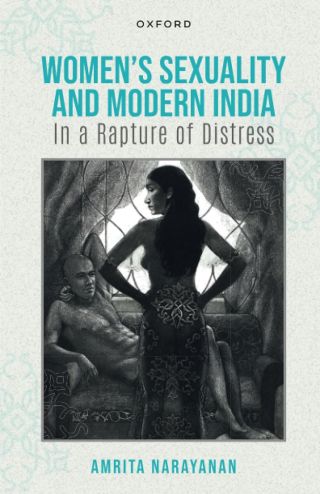

Freud’s writings reached India through the work of Girindrasekhar Bose, the first non-Western psychoanalyst who carried on a 21-year correspondence with the founder of psychoanalysis and established the Indian Psychoanalytic Society in 1922. Today, Indian psychoanalysts continue to use Freud’s ideas to undertake novel research in diverse settings. It is in this context that a recent book by Amrita Narayanan, Women’s Sexuality and Modern India (Oxford, 2023), revisits the age-old question (What do Indian women want?) for the contemporary times (age cohort of women born between 1950 and 1990). This is where the laws of Manu are challenged by the insights of the Viennese doctor. I interviewed Dr. Narayanan, whose surname ironically is traceable to the Manusmriti (an ancient Indian text that outlines women's legal restrictions), about the themes of the book on a recent visit to Goa, where she has a clinical practice.

DS: Do you agree with the psychoanalyst and writer Sudhir Kakar that "India has been a sexual wasteland for two centuries"?

AN: I think that sentence is mourning the vast tracts of people—many of them are women—who are in a sexual wasteland because cultural forces make it hard for them to partake richly of their sexuality. As Kakar’s descendent—in the psychoanalytic sense—I have the option of piggybacking on his work but to bring in a new focus of attention: how women in India manage sexuality under conditions of relative restriction.

DS: Both historical influences, British and Muslim, segregated the sexes and hid or cloistered the body, due to Victorian puritanical rules and Islamic purdha, respectively. Do you agree?

AN: Indian families feel possessive and anxious about the sexual fates of their daughters, and this anxiety gets transmitted to young girls. Of course, this anxiety about eros may have been influenced by the historical influences you describe, but in the here and now, puritanism is kept in place by physical conditions (unsafe streets) and social conditions such as the hypertrophic presence of married sexuality, as well as gossip and concerns about reputation (the proverbial “What will others think?”).

On the subject of historical influences, it’s good to remember that there is no single guilty party: the laws of Manu enforced control of women’s sexuality even before some of the British and Muslim rulers of India did. All these social forces coalesce, but the x-factor is the family’s treatment of the forces (the extent to which the family internalized these forces into their group values).

DS: Your central claim is that women in India, unlike their sisters in the West, didn’t go through the three waves of feminism in the same manner over the last century of the sexual revolution. Hence, they’re trapped in the motherhood complex between the constraints of biology and social structure. Is that correct? Or is this a flawed narrative imposed on India by the West?

AN: My claim is that India did not go to the third wave, which is of sexual subjectivity—when American and European countries did, except in small pockets. What's central to my argument is the reason the third wave was so scattered in India is that not all women wanted the freedoms that a sexual revolution brings. This may be related to their existing male partners whom they are happy with or to have become accustomed to their own aesthetics under restrictive conditions.

In particular, those women who have adapted to sex under patriarchy don't have much to gain from a revolution, because patriarchy is a cementing force as much as it is a painful and divisive force. Patriarchy confers belonging, and departs from patriarchal sexual politics—that is, independent sexuality—can fill women with fantasies of ex-communication and un-belonging. This fear of excommunication for sexual transgression is an important factor to take into account when thinking about an individual woman’s sexuality in India as it promotes sexuality that is anachronistic to the conditions of reality.

The Western narrative is that failure to revolt sexually means sexual suppression, but I argue that the absence of a sexual revolution means that India had different priorities. The absence of a sexual revolution protected a range of sexualities, including asexuality, and the preferences of women who wanted to refuse sex altogether. Sexual revolution countries do not make space for such a range because they work from the assumption that sexual liberation—telling word—is always desirable. In fact, many feminists in Europe and America complain that the sexual revolution took away choices as much as it gave freedom.

DS: Wasn’t one of the waves "equal work for equal pay"? However, only 33 percent of women in India participate in the formal economy.

AN: Yes, that was the second wave. I believe India went through all the waves except the one for sexual subjectivity. Individuals may have experienced wave 3 if they came from families that were exposed to the West, but what defines a sexual revolution is widespread media-sanctioned displays of sexual freedom for ordinary (non-Bollywood) women. Women’s desires for sexual agency and independence were largely left out of the feminist discourse until #metoo which famously caused a rift between younger and older feminists in India.

DS: With the rise of BJP, ethno-nationalism, and Hindu masculinity (men’s gyming trends), is women’s sexuality taking a back seat? What’s your opinion on recent developments?

AN: The phallic behaviors you’re describing are a backlash to women gaining agency in multiple domains. I think the rise of women’s sexual agency and freedom is agitating an already anxious masculinity.

Emerging from patriarchy is a complex process because people also unconsciously identify with it. In that way, Ashish Nandy’s telling phrase “intimate enemy” applies to patriarchy as much as to colonialism.

DS: It sounds like you’re a complete Freudian?

AN: [Giggle.] Not totally! I would say a mixture of British middle school (D.W. Winnicott, Masud Khan, Adam Phillips), a good deal of feminist psychoanalysis (Nancy Chodorow, Adrienne Harris), and then the cultural psychoanalysis, which I have from Pittu Laungani, Roy Moodley, and Sudhir Kakar (who himself is rather Freudian, as you know).

But I’m trained as an empirical psychologist, so I always have a modicum of temperance in what I believe in psychoanalysis.

DS: How much of the Freudian theory do you use?

AN: One of the central ideas in my book is how “fear of a loss of love” (Freud’s words) shapes women’s sexuality, and how girls’ upbringing unconsciously engenders that anxiety (more than it does for boys). This is of course drawn from Freud’s tripartite model and from Freud’s analysis of Ibsen in "Some Character-Types Met With in Psycho-Analytic Work."

I also talk a lot about survivor guilt—how women feel badly that they have more opportunities for pleasure than their mothers—and how this survivor guilt plays a role in women’s access to their own desires. Intergenerational survivor guilt is also a Freudian idea, if you think of his Letter to Romain Rolland ("A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis") Freud explains how difficult it was for him to have a pleasurable experience that he felt was denied to his father. I think having read Freud helped me “see” some of these patterns in my respondents and patients. I think his work on group psychology, including Civilization and Its Discontents, is still important for Indians. This is also because, as empirical studies tell us, group harmony and interdependence is still an important value for Indians. Of course, there are lots of differences from Freud that are cultural—for example, ongoing dependence is more potent in Indian parenting than the individuality and autonomy Freud emphasizes in Family Romances.