Religion

The Timing of Death

Mysteries make us ponder what we do not know.

Posted April 18, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- The timing of death has been studied from at least seven broad perspectives.

- Empirical approaches rely on statistical inferences. They explain only a portion of the factors that contribute to an outcome like death.

- They can describe tendencies that approach the universal and also those that vary among groups.

Few topics in psychology remain as poorly understood as the experience of death. Although we routinely observe life cycles in plants and animals, we don’t even have a full consensus on the definition of human death. In clear-cut cases such as a car accident with fatalities, a devastating weather event, or an intentional murder, people die suddenly and unexpectedly. Biology stops, authorized organs are procured for implants, and people move to post-death behaviors, from dealing with a non-living body to addressing the social, emotional, and material aftermath of a being’s absence from the world of the living. The “how” and “why” can sometimes be clear-cut.

Nonetheless, ambiguities and conflicts in definitions of “death” remain. Media outlets report people who were pronounced dead and were later revived. A literature describing those eager to tell of their “near-death” experience is growing. And there are the anecdotal mysteries: the 95-year-old woman who falls, breaks ribs and other bones, is hospitalized, and, a month later, returns to her own home. Surgery, a rehab hospital, and some additional physical and occupational therapy have produced a miracle. Or the person who has suffered far too many ACEs (Adverse Childhood Experiences) yet defies the statistical odds of a young demise. Or the woman who walked into the hospital with what seemed like a minor problem, suffered setback after setback, yet lived another six months.

From the perspective of my pyramid theory, here are some current definitions:

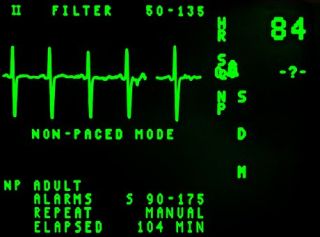

Cellular level. At the most basic level, the physics and chemistry of life, cells stop. The electrical circuits and chemicals that move — all internal communications — cease to function.

Organs. Medical personnel disagree on whether the brain or heart is the seat of life. They have observed that brain cells continue to die after we do, suggesting that when the heart stops beating signals “death” may be arguable as a definition of death.

Biological systems. When substances necessary for the preservation of life are removed, whole systems shut down, often like dominos. Impaired respiration deprives cells of the oxygen they need; a loss of hydration or nutrition removes the nutrients necessary for life to continue.

Psychological. At the psychological level, death becomes even more nuanced. On the way to death, hospice workers prefer to use the word “unresponsive” instead of “unconscious”. In truth, we do not fully understand when knowing ends. Too many people have felt the faint squeeze of a hand signaling recognition or seen the lift of an eyebrow signaling understanding. Researchers find that people continue to sense and perceive after conscious awareness has ended.

In a unique research program on the timing of death, Ellen Idler and Stan Kasl found that people are more likely to die after their birthdays than before them.1 Motivation, therefore, can explain a bit about longevity beyond that explained by biological and medical factors.

Interpersonal. At the interpersonal level, the phenomenon gets more complex and less explainable. Babies who lack the human contact they need can die from a “failure to thrive”, like Harlowe’s monkeys who were provided with wire surrogate monkeys fitted with bottles for feeding but deprived of the comfort of cloth monkeys or contact with their peers. Daniel J. Siegel is perhaps the guru of interpersonal attunement, the neurobiology of attachment, as well as damage associated with its absence.

Studies on mortality following widowhood document the power of loss of a spouse, again beyond medical and other known variables, including some that are cultural, like financial strain and the constraints it creates.

In a unique look at the role of marriage in the mortality of older married couples, Stan Kasl and Amy Darefsky and I showed that even when chronic illness and other well-known risk factors are accounted for, the style of closeness within the marriage can predict longevity — one style of relationship closeness within the couples we tracked over six years was more protective of survival than others, both for men and women, especially if the woman had ever had a child.2

Cultural. Recent years have brought data documenting the toll that “heartbreak” or other stressful experiences can have on the body and even on the “will to live”. Often related to the culture in which one lives, loneliness, a symptom of depression, or the isolation that can accompany aging (less mobility, poorer vision, and hearing) or negative stereotypes about older people, explain longevity to some extent. The opposite, social involvement and support, are associated with longer life, as is a communal compared to an individualistic perspective.

Spiritual. In a twist to the research on people dying following their birthdays rather than before the event, Ellen Idler and Stan Kasl examined the role of religious involvement (both personally and publicly) as potential protective factors in longevity. They found that, with both increasing participation in a religious community and higher self-assessed religiosity, Christian men and women were more likely to die following Christmas and Easter than prior to the holidays. Jewish men with heightened religiosity were more likely to die after (rather than before) the High Holy Days in the fall and Passover in the spring while their wives were more likely to die before the holidays. As a Jewish woman who aspires to become a “woman of valor”, I wonder if the more religious women saw themselves as unable to fulfill the roles expected of them during the holidays and so, rather than disappoint, they bowed out.

We have no answers to the mysteries of a “will to live”. People looking to “quality of life” factors can examine aspects of well-being, but do they really capture the idiosyncratic desire to watch a grandchild wed or to hold a great-grandchild in one’s arms as a new generation begins? Gratitude for and acceptance of each day, with whatever it brings, can indeed help us embrace the opportunity to be part of humanity for at least a bit longer.

Copyright 2023 Roni Beth Tower

References

1. Idler, Ellen & Kasl, Stanislav V. (1992). Religion, Disability, and Depression and the Timing of Death. American Journal of Sociology, 97, https://doi.org/10.1086/229861.

2. Tower, RB, Kasl, SV, & Darefksy, AS. (2002) Types of marital closeness and mortality risk in older couples. Psychosomatic Medicine, Jul-Aug;64(4):644-59. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-200207000-00015. PMID: 12140355.