Relationships

The Power of "Invisible" Relationships

Informal relationships are essential for change—in organizations and in life

Posted August 20, 2021 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

Key points

- Hidden social networks in organizations are vital to that organization's success.

- Informal networks with fluid, "wiggly" connections are also much more adaptable than straight-line organizational hierarchies.

- When a shifting environment requires an organization to change, that change is best initiated through the enterprise's informal structure.

If you have to solve a tough problem at work, would you rather address it in a formal meeting, complete with an agenda and follow-up emails and memos or in a chance informal encounter with a co-worker in the hallway, or even during lunch in the company cafeteria?

Most experienced workers I know would opt for informal connections over formal processes to solve problems, because informality is faster, less political, and deals with the world as it really is, as opposed to the way management says it’s supposed to be

Experts who study organizational behavior, such as Starling Hunter of Florida Atlantic University and Bill McEvily of the University of Toronto, call loosely organized, informal connections, “social networks,” as distinct from formal relationships such as boss-subordinate hierarchies.

In his book The hidden power of social networks: understanding how work really gets done in organizations, Dr Rob Cross of Babson College points out that informal social networks, despite their invisibility, are critical to the successful operation of any organization.

Cross asserts that in every organization, in addition to a formal organization chart, there is an all-important “sociogram” (a term coined by sociologist J.L. Moreno) that represents informal connections among employees of liking, respect, and friendship, and that without such informal relationships efficient work would not get done.

Whereas straight-line reporting relationships in formal hierarchies tend to be rigid and unchanging (by design), informal lines that cut across formal hierarchies are, as Cross observes, often dynamic, changing as circumstances dictate.

My wife and collaborator, Dr. Chris Gilbert, and I, who recently highlighted the importance of informal relationships in fostering innovation in our book Riding the monster: five ways to innovate inside bureaucracies, call fluid, informal connections “wiggly line” relationships to convey the loose, complex, ever changing nature of these hidden organizational connections.

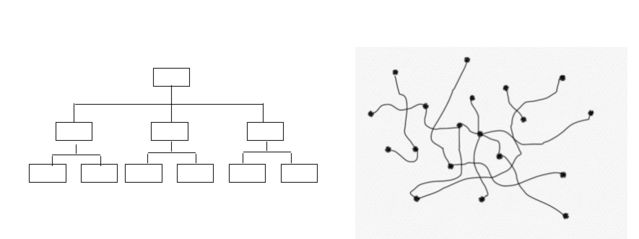

Gilbert’s and my research on innovation in bureaucracies reveals that, when trying to accomplish anything new and important in an organization, it is useful to visualize an enterprise not solely as a rigid set of square boxes connected by unchanging straight lines (as shown on the left), but as an unruly collection of dots (people) connected by ever-changing wiggly lines (depicted by the sociogram on the right).

Looking at these visuals, the reason pops out at you: boxes and lines, representing formal authority and processes are rigid and unchanging, whereas wiggly lines of informal relationships are flexible, adaptable, and, above all, changeable as a fast-changing world requires.

In the informal unit called a family, for instance, it used to be that parents taught their children important skills, not vice versa. But in today’s dynamic digital world, it’s not uncommon for children to teach their parents or grandparents how to use a computer or mobile device.

And so it is in the workplace: When an organization’s environment changes in a major way (e.g. new technology or new competitors), wiggly-line relationships can change far more quickly and pragmatically to adapt to the changes than can the formal, straight-line hierarchies, because informal relationships transcend and bypass red tape, process, budgets and all of the other baggage that weighs down, and slows down bureaucracies.

One of the innovators featured in my book with Gilbert, Mike Goslin of Disney, responded to the fast-changing world of digital entertainment by exploring a chance, informal encounter with a former colleague who worked at Lenovo, to partner with that consumer electronics company to bring a best-selling Augmented Reality system (Star Wars Jedi Challenges) to market in less than a year—a blistering pace of development that many Silicon Valley startups could not match.

How did Goslin pull it off? He followed up the chance encounter with a series of speedy handshake deals with Lenovo and other key partners in restaurants and bars, deals that he later convinced his management to approve.

The takeaway lesson from Gilbert's and my research, and from preceding studies of informal relationships in rigidly structured, hierarchical organizations, is that change agents desiring to transform anything significant about their organization, from the way it handles diversity to the products and markets it pursues, should never restrict their efforts to convincing the “suits” to change course.

Although getting buy-in from the suits to make fundamental change is ultimately necessary, the wiggly-line concept suggests that change agents should never start their campaigns for transformation by tackling the suits head-on. Instead, people who want change should focus first on what changes most easily in an organization: fluid, informal relationships comprising what Cross calls “seemingly invisible” social networks.

Although this stealth approach might seem counterintuitive, inasmuch as the suits are the ultimate deciders, it makes sense when you consider that, according to Starling Hunter’s research on hidden social networks in enterprises, suits themselves belong to multiple hidden social networks (i.e. with wiggly-line relationships). And suits, at the end of the day, are just like the rest of us: giving greater weight to ideas first heard through informal channels from people they trust, respect, and like, than through formal channels.

Bottom line: wiggly lines ultimately do intersect with straight lines, and, when it comes to organizational change, the fastest way between two points is actually a wiggly line, not a straight one.