Psychiatry

If You Want a Better Psychiatry, Go Back 200 Years

What does psychiatry during the Reign of Terror have to teach? A lot.

Updated July 31, 2023 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Key points

- Philippe Pinel's moral treatment models a human-centered, not med-centered, psychiatry.

- The best impulses of humanity, Pinel tells us, can be inseparable from its madness.

- Only understanding my psychosis has made me whole.

I once, all night, heard a newscaster’s voice speaking out of a radiator. My mother had just died. It was a male voice so monotonous I can’t remember much that’s specific. Weather, thefts, a car stalled on a bridge. The voice scared me but had little content. Snippets of news repeated and repeated, the way you hear a radio tuned in on a monotonous drive, when you keep it playing but barely know it’s on.

Madness "A Socially Awkward Drive for Infinity"

Madness? A philosopher named Wouter Kusters calls madness a “socially awkward drive for infinity in a finite world.” This idea illuminates a lot of what I think we miss about “mental illness.” Whatever that state might be for someone, however much it needs to go away (and I know how desperate that need can be), no consciousness is capable of the absence of meaning.

Even existential meaning, to use an overused word.

That would be meaning about what it is to be us, as in humans, in this world. Depression is often sadness not just about oneself, but how life itself falls short. Depression, mania, being on the spectrum, traumatic responses, and so on can be madnesses, in Kusters’ sense. Beyond the social standard of well-behaved brains. These are standards with no stable historical or cultural rules, just those of the present moment and the present place.

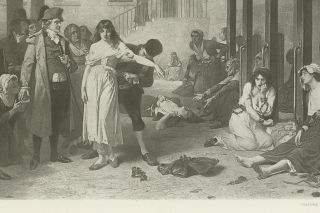

In 1794, the great psychiatric reformer Philippe Pinel said in a speech that “I have nowhere met, except in romances, with fonder husbands, more affectionate parents, more impassioned lovers, more pure and exalted patriots, than in the lunatic asylum.” He addressed many leading minds of France. Pinel took over a Paris asylum, Bicêtre, where patients lived with starvation, whips, and shackles. One man had been chained for more than four decades. Some had lost the ability to walk.

At the time, for an admission fee of a few cents, people went through asylums gawking, as if they were zoos. They, or wardens, could taunt and even lash patients to get a response. Within a year Pinel released 25 out of 200 in Bicêtre back into the world, ready to return to the lives they’d lived before. This was an unheard-of level of success.

The Best Impulses of Humanity, and Its Madness

Pinel told his Paris audience that his patients’ “present state derives only from a vivid sensitivity and from psychologic qualities we value highly.” The best impulses of humanity, in other words, can be inseparable from its madness. I cannot call this an idea ahead of its time; the idea has yet to truly have its time.

We have moved far from Pinel, whose ideas changed psychiatry throughout Europe. In 1978, influential psychiatrist Gerald Klerman said there exists within minds “a boundary between the normal and the sick.” That idea, of mental states as “illness” like any other illness, caught on. In 1989, psychiatrist Samuel Guze said there could be “no such thing as a psychiatry that is too biological.” Most of us have grown up in the era of biological psychiatry, brain chemistry, and medications to fix “chemical imbalances.” Our culture now medicates more people more heavily than it ever has, only to face increasing amounts of distress, a shift that began long before Covid.

Unlike our normal practice of delivering psychiatric meds in 15-minute, every-few-month visits, Pinel spoke to patients daily and took long notes. He wrote that the mind doctor’s job was to understand a patient intimately, to know their “hopes and their dreams.” While it is a great art for a doctor to know how to administer medicines, Pinel said, it is a far greater knowledge to know when to “suspend or altogether omit them.”

Here he might find the 21st century most at fault.

Pinel’s great work was his Treatise on Madness, and maybe that’s why I like the term “madness” so much. I like the term “experiencer,” for those of us who experience non-consensus thought. And "neurodiversity," to show connection with biodiversity—the more kinds of minds we have, the richer our conscious ecosystem. And the greater our chances for solving our novel problems, novel because we ourselves in unprecedented ways create them.

The Mind in Relationship With The World

But I think even celebrating the social value of difference can miss some points. What we call illness of the mind is a human experience that exists in relationship to the world around it and must be understood that way. Always.

At the time of my newscaster’s voice, I’d been soaked for months in my mother’s dying. She had Alzheimer’s. A fraught relationship became even more fraught, then bang smash it was over. That monotone forced me to soak in the this-world. With its traffic jams, bad weather, and non-death problems. It dragged me back to my existence. I flew home feeling like some long arm-wrestle with things outside of this world was over.

It took many years to understand that night’s voice wasn’t just being one of “the sick.”

I have a friend who tells me that if you want a better psychiatry, wait 100 years. I tell him, Or go back more than 200. So yes, I ask that we reconsider a medical model that would be rejected as insuffient by a man who lived in the age of the lash, the fetter, and the Reign of Terror. We have much to learn.

References

Kusters, Wouter. A Philosophy of Madness: The Experience of Psychotic Thinking, translated by Nancy Forest-Flier. Boston: MA, MIT Press, 2020.