Vagus Nerve

How the Polyvagal Theory Inspired My Parenting

Parenting children with autism.

Posted February 2, 2024 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

Key points

- Ways in which caregivers respond to their children's emotions can impact their coping and physiology.

- Parental meta-emotions are a significant source of safety cues that help children cope with emotions.

- The polyvagal theory offers a schema that appreciates the impact of nonverbal cues on nervous system activity.

Every parent knows that emotions are oftentimes contagious. Whenever my own mood is jovial and calm, my children seem to experience fewer meltdowns, while my experience of stress seems to have the opposite effect on them (even with my best attempts at masking). Appreciating this contagion quality of emotion makes nourishing my own nervous system a priority for me, through making time for activities that keep it calm and rested (like exercise and mindfulness).

Attachment theorists concur that ways in which caregivers respond to their children's emotions impact children’s relationship with their inner experience, their coping, even their physiology.

Similarly, when the polyvagal theory came out in 1994, it offered yet another paradigm for appreciating the impact of parental responsiveness on children’s coping with emotions and their physiology.

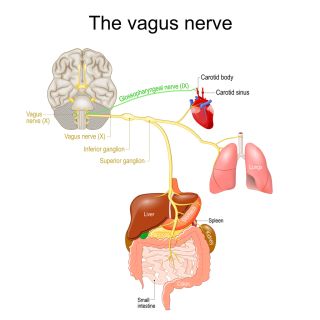

Polyvagal theory is a collection of hypotheses about the functioning of the body’s vagus nerve and how it impacts individuals’ experiences of social connection, calm and safety, as well as trauma, coined by Stephen Porges, Ph.D.

At the center of the polyvagal theory is the vagus nerve, the largest nerve in mammals that extends from the brain’s cerebellum into the body’s many major organs and peripheral senses. According to the polyvagal theory, the vagus plays a key role in informing the brain about what is happening within the body, like a messenger that reports to the brain on the functioning of the body’s major organs as well as its peripheral sensory experiences.

Dr Porges suggested that the major facial muscles involved in facial expression reveal important safety cues about whether an individual’s nervous system is receptive to engaging with others and in a parasympathetic state of calm and restoration, or whether an individual is feeling threatened and unsafe.

Our nervous systems are in a continual process of perceiving information from the environment, including from the facial expressions and voice of others, continually picking up on cues of safety or danger. And, they continually shift between states of calm and safety (associated with the activity of the ventral vagus) and fight-flight mobilization, or a shut-down response if the fight-flight mobilization is insufficient to cope with a threat or demand.

Whereas biological psychologists have recently disputed some of the underlying assumptions of the polyvagal theory, questioning the impact of the dorsal (back) vagus on the freeze response, or questioning the assumption that the mammalian vagus circuit is indeed unique to mammals, the vagus nerve and its role in the processing of information from the environment and our experience of emotion continues to be researched.

Dr Porges suggested that the most recently evolved ventral vagal circuit can suppress the activity of the more primitive dorsal vagus through exposure to safety cues, whether social or internal safety cues such as applying slow exhalations to calm the body. Even though the evolutionary hierarchy underlying the various parts of the vagus has been disputed by biological psychology researchers, Dr Porges raises awareness of the importance of safety cues on the triggering of the calming response of the vagus nerve, within interpersonal connections.

Parenting, meta-emotions and the nervous system

According to Gottman, parental attitudes and feelings about emotions (a term he referred to as meta-emotion) are another significant source of safety cues that impact children's coping with emotion and even their physiology.

Gottman found that parental meta-emotions, or the thoughts and feelings parents have about their own and their children’s emotions, are key in either nurturing safety and connection in their attachment, or in cases where meta-emotions are laced with criticism, an experience of a lack of safety.

Examples of meta-emotions can include apprehension (for example if a parent wishes to protect their children from feeling angry due to perceiving anger to be destructive) or resentment (for example towards a child’s sadness, fueled by a concern over their lack of gratitude and appreciation). Meta-emotion can be associated with a critical attitude, or a validating one.

Meta-emotion can be revealed through parental micro-expression, and aspects of the Polyvagal theory offer a handy schema that helps to appreciate the impact of nonverbal cues on another person’s nervous system activity.

Nurturing constructive meta-emotions and an experience of safety and calm

Gottman suggested that there are many attitudes and practices that support parents in nurturing an experience of safety and connection with their children.

These include viewing “negative” emotions as an opportunity for intimacy and teaching, which automatically infuses them with positivity and reduces their sense of threat, or assisting children with verbally labelling their emotions, which helps to connect their emotional experiences with prefrontal cognitive processes including reflection (which, in turn, mediate their emotional experience). Other strategies that can support parents in helping their children experience safety and connection in the midst of experiencing an emotion include problem-solving with their child, setting behavioral limits, and discussing goals and strategies for dealing with the situation.

I am appreciative of the polyvagal theory in inspiring within me a greater appreciation of the impact of nonverbal cues, including ones associated with above mentioned parenting coaching practices and meta-emotion attitudes, on how I communicate cues of safety and calm to my children.

Despite a lack of evidence in relation to the polyvagal theory’s underlying assumptions (such as the role of the dorsal vagus in the freezing response or the evolutionary assumptions underlying the various vagus circuits) and its criticism for oversimplifying the view of the nervous system, polyvagal theory shines a light on the importance of the vagus nerve to our experience of emotion and interpersonal connections (which continues to be researched). For me, personally, it continues to inspire an appreciation and awareness of the impact of my nonverbal cues and emotional coaching practices on nurturing cues of safety and calm within my children.

References

Gottman, J. M., Katz, L. F., & Hooven, C. (1996). Parental Meta-Emotion Philosophy and the Emotional Life of Families: Theoretical Models and Preliminary Data. Journal of Family Psychology, 10(3), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.10.3.243

Grossman, P. (2023). Fundamental challenges and likely refutations of the five basic premises of the polyvagal theory. Biological Psychology, 180, 108589–108589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2023.108589

Insel, T. R., & Young, L. J. (2001). The neurobiology of attachment. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience, 2(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1038/35053579

Norman, E., & Furnes, B. (2016). The Concept of “Metaemotion”: What is There to Learn From Research on Metacognition? Emotion Review, 8(2), 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914552913

Simon, R., & Porges, S. W. (2012). Understanding polyvagal theory : emotion, attachment and self-regulation. Psychotherapy Networker.