Coronavirus Disease 2019

Why Do People Develop a Mental Disorder?

Your response to the coronavirus stems from evolution.

Posted April 4, 2020 Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

Evolutionary psychiatry can help people accept their own or another’s mental illness. It provides one way to understand why the illness occurred. Key to an evolutionary understanding is the way natural selection maximizes passage of one’s genes to the next generation: An emotion-based warning system alerts us to potential dangers and opportunities.1 But some think it goes awry in mental illnesses. Let’s probe this a bit.

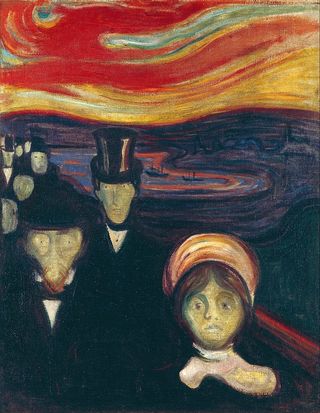

Emotions mediate our interactions not just for basic survival and reproduction, but also for all higher-level life requirements, especially successful interactions with others in our complex society.1 We express our emotions nonverbally (crying, arms crossed) and verbally as our primary means of interfacing and responding to people (and other parts of our environment, such as a virus), and there are accepted norms for how we do this.

When such emotional communication falls outside accepted norms, many experts proclaim a mental illness. Evolutionary psychiatry tries to understand "why" and "if" people, their emotions in particular, fall outside the norms.2-4 Some evolutionary psychiatry schools propose that mental disorders are not adaptive but that they stem from an over-responsiveness of normal emotion-based survival mechanisms.2

First, then, what are normal mechanisms? As you’d expect, feelings and emotions of anxiety/fear undergird the vigilance we need to detect harm in the environment, leading us to “fight or flight.” Sometimes, though, fight or flight is not possible or not successful and to continue would deplete one’s energy needed to survive.5 Such humans (or animals) normally feel helpless and/or hopeless and withdraw strategically to conserve energy and avoid more of the stress causing the fight/flight.6,7

Go to any dog pound as an example. The recent admissions continuously and frantically bark and claw at their cages. In contrast, there are dogs who lie quietly in the backs of their cages. They’ve been there for a couple of weeks, and after finding out that all the energy expended early on went for naught, they're now conserving it for a better time. Both emotions (anxiety and hopelessness/helplessness) are normal, healthy, and adaptive responses that promote survival. Can you think about normal human responses you’ve seen or experienced with fight/flight or withdrawal? Maybe when irritated at being cut off in traffic? Where are most of us now on this spectrum with the very real-life threat of the coronavirus?

These warning signals are well ingrained. We respond to everything from a potential death threat, such as a gun-wielding burglar, to some benign social act like a sour look from your boss. We experience all levels of warning, meaning that low-grade anxiousness or helplessness and hopelessness occur frequently.1

When we sense the problem is innocuous, the emotions quickly recede. But they don’t disappear, rather falling to subconscious baseline levels for continued, ongoing monitoring as we proceed with our normal lives.5 We respond with actual fight/flight or withdrawal (physical, emotional) only when a problem is perceived as a bonafide threat.

Some have likened this continuous scanning to a smoke detector system that goes off at the slightest hint of smoke, even though a true fire is rare.2 It’s best that we experience the minor inconvenience of shutting off a false alarm occasionally than a devastating fire when there is no smoke detector.

For some people, though, the alarm goes off too often, is too loud, is too persistent—in response to what would not be a threat to most. These people respond excessively to everyday stresses. Some stew and worry constantly, while pervasive helpless or hopeless feelings force others into a predominant withdrawal mode. The over-reactive anxious feelings become clinical anxiety. The exaggerated helpless and hopeless feelings become clinical depression.7

There’s, however, another take on this idea in evolutionary psychiatry. The other view posits that the apparently excessive responses themselves are actually adaptive and protective.3,8 Here’s how. Most experts have long believed in an ideal state of human growth and development, meaning that people not achieving the norm are impaired, as in the above examples of clinical anxiety or depression.

The new view is that there is no ideal human state.8 Given quite atypical stresses in their environments, often far from the experiences of so-called normal people, many persons with a mental illness may be responding adaptively and appropriately to their unique situations.

Although those with mental disorders stemming from severe environmental stressors may appear less fit, they are responding in a way that is or previously was adaptive, the best way to survive a terrible situation such as childhood abuse. They have a certain body wisdom guiding them in how best to survive, their survival issues far different from so-called normal people.

Nonadaptive as they sometimes appear, we must recall that evolution works backward and does not anticipate future events. As well, it takes time for evolution to change.

What works under certain developmental conditions does not necessarily work under others.8 There is no ideal; what is optimal for one person may not be for another. Perhaps we need to reflect on the old adage that we “walk a mile in his moccasins” before labeling them abnormal.

References

1. Buck R. Emotion—A Biosocial Synthesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2014.

2. Nesse R. Good Reasons for Bad Feelings—Insights from the Frontier of Evolutionary Psychiatry: Dutton; 2019.

3. Abed R, Ayton A, St John-Smith P, Swanepoel A, Tracy DK. Evolutionary biology: an essential basic science for the training of the next generation of psychiatrists. Br J Psychiatry 2019;215:699-701.

4. Grunspan DZ, Nesse RM, Barnes ME, Brownell SE. Core principles of evolutionary medicine: A Delphi study. Evol Med Public Health 2018;2018:13-23.

5. Engel GL. Anxiety and depression-withdrawl: the primary affects of unpleasure. International Journal of Psychoanalysis 1962;43:89-97.

6. Schmale JA. Needs, Gratifications, and the Vicissitudes of the Self-Representation—A Developmental Concept of Psychic Object Relationships. Psychoanalytic Study of Society 1962;2:9-41.

7. Schmale AH, Jr. Relationship of separation and depression to disease. I. A report on a hospitalized medical population. Psychosom Med 1958;20:259-77.

8. Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond risk, resilience, and dysregulation: phenotypic plasticity and human development. Dev Psychopathol 2013;25:1243-61.