Psychiatry

Pathological Belief: The 5 Stages of Ideological Commitment

Deep ideological passion carries an escalating risk of distress and dysfunction.

Updated October 31, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The potential pathology of belief is less a matter of what people believe than how they believe.

- Cognitive dimensions of belief—like conviction and preoccupation—can be modeled as a pathological continuum.

- Greater ideological commitment carries a growing risk of distress, social conflict, and potential violence.

What Makes a Belief Pathological?

Since the start of this blog in 2014, Psych Unseen has focused on the psychology of false beliefs ranging from pathological delusions to a variety of “delusion-like beliefs” that inhabit the grey area between mental illness and normality.

Navigating this nebulous space can be tricky. All too often, when we attempt to distinguish the pathological from the normal, we get distracted by how unfamiliar, unpopular, or implausible a belief might seem to us. Even in psychiatry, there has been a long tradition of guiding the assessment of delusions based on the apparent “bizarreness” of a belief, where “bizarre” was loosely defined as something not possible.

But several studies have demonstrated that the inter-rater reliability of bizarreness—that is, the ability for raters to agree on what’s possible or not—was quite poor, so the concept of bizarreness was all but eliminated in the DSM-5.1,2 And for good reason—whether used by psychiatrists or laypeople, the intuition that “if a belief seems crazy, it must be crazy” is a biased and narrow-minded perspective that risks the overdiagnosis of “false positives” by failing to account for the rich diversity of normal belief. A quick survey of the wide-ranging heterogeneity of religious belief should make this abundantly clear, despite the fact that human beings still continue to kill each other over who’s right about such things.

Near the start of my academic career, following the work of cognitive psychologists like Dr. Emmanuelle Peters at King's College London, I concluded that the pathology of belief should be judged less based on content (i.e., what one believes) than on the cognitive dimensions of belief, such as conviction (i.e., how strongly one believes), preoccupation (i.e., how much time and mental energy is spent thinking about the belief or its implications), and distress (i.e., how much emotional upset the belief—or the fact that others disagree with it—causes).3,4 This conclusion acknowledges that beliefs aren't an all-or-nothing phenomenon—just how passionately, stubbornly, and defensively we hold our beliefs is better represented along a continuum of commitment. Building upon similar efforts to model conspiracy theories, anti-science belief, religious credence, and political dogma along a continuum of conviction and related cognitive dimensions,5,6 I now find it useful to characterize beliefs according to five stages of ideological commitment.7,8

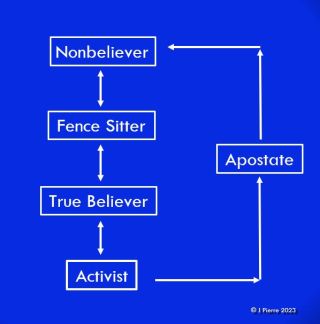

The Five Stages of Ideological Commitment

Within this stage-wise model, an “ideology” is defined as a shared belief system or “worldview” made up of not only factual beliefs that are potentially falsifiable, but also values (i.e., beliefs about what’s important) and morals (i.e., beliefs about what’s good or bad and right or wrong) that are more subjective.

► Nonbelievers are uncommitted to the ideology in question and instead tend to form and maintain beliefs dispassionately with cognitive flexibility, intellectual humility, and analytical thinking.

► Fence-sitters hold ideological beliefs with ambivalence, often based on mistrust of mainstream narratives and expert opinion.

► True believers hold ideological beliefs fervently with high conviction and passion, maintaining faith through cognitive dissonance and increasingly equating belief with identity.

► Activists are true believers for whom belief is not enough—action is necessary to stand up for, advance, or defend an ideological cause.

► Apostates have scaled back or abandoned their previous ideological commitment in favor of a return to non-belief.

While I have often characterized conspiracy beliefs according to the five stages of ideological commitment, the stages are just as well suited to other types of ideologic beliefs—like religious credence and political dogma—that ideological opponents often inappropriately claim to represent “mass delusion” or “mass psychosis.”

While this model doesn't claim that ideological conviction is pathological per se, a testable underlying hypothesis is that deepening ideological commitment across the five stages is associated with an escalating risk of personal distress, interpersonal conflict, and dysfunctional behavior, including violence, that are often defining features of psychopathology. Over the next several blog posts, I’ll make this case while diving further into the details of each stage and discussing its associated risk of dysfunctional behavior. Stay tuned.

For more on pathological belief and the 5 Stages of Ideological Commitment:

References

1. Cermolacce, M, Sass L, Parnas J. What is bizarre in bizarre delusions? A critical review. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2010; 36:667-679.

2. Spitzer RL, First MB, Kendler KS, Stein DJ. The reliability of three definitions of bizarre delusions. American Journal of Psychiatry 1993; 150: 880-884.

3. Peters ER, Joseph SA, Garety PA. Measurement of delusional ideation in the normal population: Introducing the PDI (Peters et al. Delusions Inventory). Schizophrenia Bulletin 1999; 25:553–76.

4. Pierre JM. Faith or delusion? At the crossroads of religion and psychosis. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 2001; 7:163–72.

5. Franks B, Bangerter A, Bauer MW, Hall M, Noori MC. Beyond “monologicality”? Exploring conspiracist worldviews. Frontiers in Psychology 2017; 8:861.

6. McCauley C, Moskalenko S. Understanding political radicalization: The two-pyramids model. American Psychologist 2017; 72:205-16.

7. Pierre JM. Down the conspiracy theory rabbit hole: How does one become a follower of QAnon? In: Miller, M (ed) The Social Science of QAnon, Cambridge University Press: Cambridge UK. In press.

8. Pierre M. Conspiracy theory belief: A sane response to an insane world? Review of Philosophy and Psychology. Submitted.