Creativity

Fragile Brilliance: The Troubled Life of Herman Melville

Part I of a series examining Melville's life and struggle with mental illness.

Posted August 6, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Herman Melville's life was characterized by periods of euphoria, grandiosity, and remarkable energy, alternating with deep depression.

- Against the backdrop of depression after the death of his brother, Herman Melville summoned a boundless drive to write.

- It has been said that Herman Melville's rewriting of "Moby Dick" was carried out in an excited, even frenzied state.

In an earlier post, I described Abraham Lincoln’s struggles with depression to introduce the topic of the possible relationship of depression to achievement. In this two-part post, we’ll consider the association of bipolar disorder to creativity, and begin by looking at the unsettled—and very productive life—of Herman Melville.

Early years

Melville was born in New York in 1819, his mother from a prominent Albany family of Dutch descent, and his father Allan, an importer of French dress goods. Both sides of the family had roots in the American Revolutionary War; his paternal grandfather had participated in the Boston Tea Party and served as a major in the Revolutionary army, while his maternal grandfather was a general known for defeating the British blockade of Fort Stanwix in the Saratoga campaign of 1777.

The family business of selling French handkerchiefs, kid gloves, stockings, and other goods went well in Herman’s early years. His father moved the family into a series of ever-grander houses, stretching his resources but promoting the image of prosperity. By 1830, however, there were setbacks. In an effort to maintain appearances, Allan took out unwise loans and went deeper into debt. Finally, with the rent three months overdue, he hastily moved the family to Albany. There he worked as a clerk at a cap and fur store, though he tried to give his acquaintances the impression that he was the manager. In December 1831, when returning from a trip to New York to deal with his debts, he was forced to ride for two days in an open carriage in freezing weather. Shortly thereafter he developed a fever and delirium, frightening the family with his ravings, and died in late January.

After Allan’s death, the oldest son, Gansevoort, set himself up in the cap and fur business. Herman, who had left school the previous year due to family financial difficulties, worked first in a bank and then at the store. In 1835, he was able to attend school, but two years later a financial panic led to the bankruptcy of the family business and his withdrawal. He worked first on a farm, then briefly as a schoolteacher, and unsuccessfully tried to obtain work on the Erie Canal.

Setting out to sea

Unable to find steady employment, Herman followed Gansevoort’s advice to go to sea. Gansevoort got him a position as a cabin boy on the merchant vessel St. Lawrence. Four months later he returned from a round trip to Liverpool. He took a teaching position in a school that folded and failed to pay him. Unable to find a steady income, he signed on to the whaling ship Acushnet, sailing around Cape Horn into the Pacific.

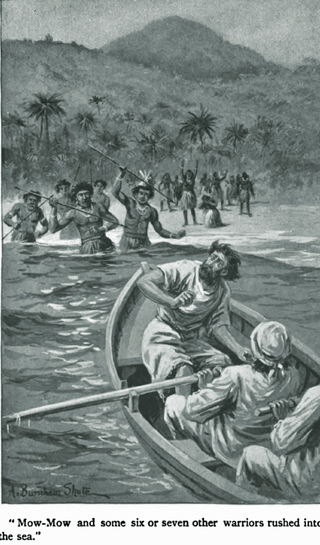

A year and a half into the voyage, the harsh conditions led him and a friend to jump ship in the Marquesas Islands. There, they were captured by the Typees, a cannibal tribe whose interests in him fortunately did not extend to the culinary. After a month, he managed to escape on the Australian whaler Lucy Ann, only to be later accused of mutiny and jailed in Tahiti. He managed to escape, and later, working as a harpooner, made his way to Hawaii. Tiring of work there as a store clerk, he enlisted as an ordinary seaman on a U.S. Navy frigate and sailed to Boston in 1844.

Writing career

Happily, things were going better at home. Gansevoort was now a diplomat stationed in London. With less financial pressure, Herman now had time to write. In 1846 he published Typee, a romanticized version of his experiences among the cannibals, and in 1847 he came out with the sequel Omoo, based on his voyage on the Australian whaler, the mutiny, and his subsequent jailing.

Both were successes, and Melville developed a reputation as a writer of adventuresome tales. Any happiness he achieved was tempered, though, by the death at age 30 of Gansevoort, who had written him a very depressive letter from London, and died displaying possibly psychotic symptoms sometime thereafter. In addition to the emotional impact, the family was now more dependent on Melville’s writings. Financial pressure became even greater when he married Elizabeth Shaw, daughter of a prominent Massachusetts judge.

In a burst of feverish energy, he tried to regain both his reputation and his finances, producing two more novels in only four months. Redburn recounted the experience of a young American, the son of a gentleman, among the cruder sailors in the shabbier parts of Liverpool. White-Jacket, based on Melville’s experiences with the U.S. Navy frigate, described the harsh life of the crew. Both carried a darker undertone than his previous work, perhaps influenced by Melville’s readings of Shakespeare, notably King Lear.

Moby Dick

In 1850, Melville met Nathaniel Hawthorne at a picnic and felt he now had a kindred spirit. He had been influenced by Hawthorne’s Mosses from an Old Manse, and in a review described it as richly ‘shrouded in blackness, ten times black’ (1). At the time, Melville had already been working on Moby Dick, and perhaps under Hawthorne’s influence, he moved beyond writing an exciting sea tale to one which took on allegorical qualities as well as exploring themes such as obsession and revenge.

There is some suggestion that this rewriting of Moby Dick was carried out in an excited, even frenzied state, which sometimes came through in the writing, as in this passage: ‘Give me a condor’s quill! Give me Vesuvius’ crater for an inkstand! (2). He worked very long hours, often forgetting to eat. He once teasingly instructed a friend to supply ‘fifty fast-writing youths…because since I have been here, I have planned about that number of future works, and can’t find enough time to think about them separately.’ (3). The writing itself has been interpreted by some to display flight of ideas, rapid changes of topics often seen in episodes of mania; the plot is intermingled with digressions (4) which might include for instance factual material about equipment for whaling, or speculations on the meaning of colors.

In the next post, we will see how these periods of seemingly boundless energy and drive to write were matched with other times of deep depression, a pattern which Melville likened to the soaring and plunging flight of a Catskill eagle. We will look at both his family history and personal experience in examining the intricate relationship between his illness and his work.

Portions of this article are adapted from Fragile Brilliance: The Troubled Lives of Herman Melville, Edgar Allan Poe, Emily Dickinson, and Other Great Authors.

References

1. Mellow, James R. Nathaniel Hawthorne in His Times. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980, p 335. ISBN 0-395-27602-0.

2. Melville, H.: Moby Dick, or the Whale. Penguin Classics, New York, 1992 edition.

3. Leyda, J.: The Melville Log: A documentary life of Herman Melville, 1819-1891, Volume 1. Harcourt, Brace and Co., New York, 1951, p. 401, cited in: Ross, J.J.: The many ailments of Herman Melville (1819-1891). J. Med. Biog. 16: 21-29, 2008.

4. Orr, L.: Digression and nonsequential interpolation: the example of Melville. J. Narrative Technique 9: 93-108, 1979. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30225664?seq=1