Neuroscience

The World War II Era Roots of Modern Neuroscience

The discoverers who suffered at the hands of the Nazis.

Posted January 4, 2022 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Modern neuroscience, like psychopharmacology, grew from the World War II era.

- Many key discoveries were made by physicians and scientists who fled the Nazis or suffered at their hands.

- Among these were Hans Berger, whose pursuit of "psychic energy" led to the discovery of the human EEG.

- Similarly, Otto Loewi, who first demonstrated chemical neurotransmission, was jailed by the Gestapo for accepting the Nobel Prize.

In a previous post, I described the roots of modern psychopharmacology in the work of physicians and scientists who fled the rise of Naziism to England, the U.S., and Canada. Among these were Heinz Lehmann, who played an important role in the clinical introduction of chlorpromazine (Thorazine), Frank Berger, who developed the first modern tranquilizer, and Leo Sternbach, who synthesized the benzodiazepines.

It’s important to remember, though, that the beginnings of modern neuroscience also come from the pre-war and World War II era. Among the contributors were Hans Berger, who developed the human EEG, and Otto Loewi, who contributed to understanding how cells communicate. Both suffered during the rise of Naziism. Their stories ended very differently, though—one in tragedy and the other with escape and a new life.

Hans Berger and the Pursuit of "Psychic Energy"

Hans Berger, born in 1873 in Neuses, Germany, was the son of the head physician of a nearby asylum, and the grandson of the poet Friedrich Rückert, to whose work he became very attached. He was a shy, introspective youngster with little interest in medicine, but was drawn to astronomy.

After a semester at the university in Jena in 1892, for reasons which have never been well described, he interrupted his studies and enlisted in the cavalry. There, he had an experience that changed his life. One day, his horse unexpectedly reared up, throwing him to the ground in front of a horse-drawn cannon. Though it appeared likely that he would be run over, the driver managed to stop in time, and Berger was saved.

At apparently that same time, his sister, who lived some distance away, was overcome with a feeling that her brother was in danger, and appealed to her father to send him a telegram asking if he were okay. The telegram seemed to Berger to be evidence that "spontaneous telepathy" had taken place, and after returning to Jena, he changed his studies to medicine with the goal of determining what kind of "psychic energy" might have been involved.

Following graduation in 1897, he worked in the psychiatry and neurology clinic in Jena. After eight years devoted to studying blood flow in the brains of patients with skull fractures, he returned to the question which had led him into medicine. He began by trying to determine whether electrical activity could be measured in the human brain, as had previously been found in animals.

Berger’s studies were interrupted by World War I, in which he worked as an army psychiatrist; afterwards he returned to Jena and ultimately became the chief of psychiatry there. Some thought that he appeared to lead a kind of double life: Outwardly, he seemed rigid and humorless, while his private time was filled with poetry and recording spiritual thoughts in his diary.

He was also very persistent, and in 1924, he used a vacuum tube amplifier to record the first electroencephalogram (EEG), a term he coined, in a 17-year-old boy who was undergoing neurosurgery. He refined the technique, later recording from the periosteum membrane covering the skull, and then from the surface of the scalp, where he studied, among others, his own children.

By 1929, he had gained enough experience that he felt comfortable publishing his first paper, and over the next years described EEG changes with age, mental activity and sleep, and in persons with brain tumors.

Initially he was met with indifference and skepticism. By the mid-1930s, he gained the support of the English electrophysiologist Edgar Adrian and gave talks with him at meetings. He hoped to travel with him to the U.S., but was unable to because of the imminence of war. By that time, the EEG was recognized internationally as a useful clinical tool.

In 1938, the Nazis had taken control of Berger’s university. Exactly what happened to him is a matter of debate. Early accounts indicated that at age 65 he was forced to retire, and told that he could never again work on the EEG. Later records suggested that he remained at the university and was pressured to cooperate with the Nazis. It is known that he became very depressed, and in 1941 he hung himself in his own clinic.

Otto Loewi and the Stuff That Dreams Are Made Of

Otto Loewi was born in 1873 in Frankfort, Germany, the son of a well-to-do wine merchant. He was drawn to classical languages and art, and planned to study art history, but was persuaded by his father to go to medical school.

Once at the University of Strasbourg in 1891, he tended to skip his required classes in favor of those in the humanities. He barely squeezed through the first major examination, and had to spend a remedial year before gaining enthusiasm for his studies.

After graduation in 1896, Loewi worked briefly in Frankfort and London, and settled at the University of Graz in Austria. He had a newfound interest in how nerve cells communicate from his work on the autonomic nervous system with the English physiologist Henry Dale. At the time, there was contention between those who believed that the crucial aspect was due to chemical transmission and those who were in favor of an electrical explanation (less elegantly referred to as the "soup" and "sparks" schools).

One evening in 1920, he was reading and drifted off to sleep, later awakening with an idea for an experiment. He hastily scribbled down his ideas and returned to sleep. The next morning, to his consternation, he was unable to read his hastily written notes. After what he later described as the longest day of his life, he went to sleep the following night and awakened with the same idea. This time he arose, went to his laboratory, and conducted the experiment which changed neurophysiology.

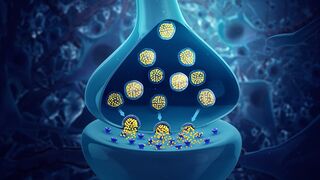

In essence, he had found that the vagus nerve releases a substance, later found to be acetylcholine, which affects receptors in heart tissue, a finding supporting the chemical view of transmission. As a result, Loewi and Henry Dale were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1936.

March 12 of 1938 brought the Nazis Anschluss, the invasion of Austria, and that night Loewi was awakened by a dozen stormtroopers; he and two of his sons were arrested and imprisoned by the Gestapo. He was charged with violating Hitler’s ban on citizens accepting the Nobel Prize.

News of Loewi’s arrest reached the International Physics Congress in Zurich, and the ensuing protests led to his release two months later, after he was forced to turn over his Nobel Prize money to a Nazi bank. He left for England in September of 1938 and later moved to the U.S., where he taught at New York University. And thus it was that an unpromising medical student, enthralled with the humanities, went on to change the direction of neuroscience.

Many other discoveries came from these years, Advances in nerve regeneration came from Ludwig Guttmann, a neurosurgeon who fled Germany for England. We'll see others, including the recognition of the EEG sleep stages by Alfred Lee Loomis and the characterization of the neuronal action potential by Alan Hodgkin and Andrew Huxley, in a later post.

Portions of this post were adapted from Trial by Fire: World War II and the Founders of Modern Neuroscience and Psychopharmacology.