Evolutionary Psychology

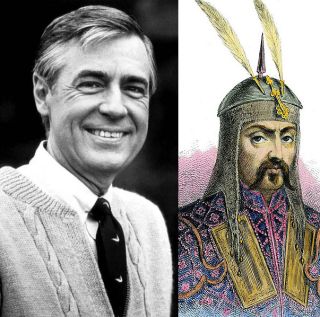

Who's a Better Role Model: Genghis Khan or Mr. Rogers?

It's not just a philosophical question—science can guide your choice.

Posted November 4, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- There is a common misconception that selfish genes mean that people are designed to be selfish.

- This misconception is linked to a philosophical mistake called the naturalistic fallacy.

- The same misconception is also based on a misreading of the psychological and anthropological data.

- The evidence suggests that selfishness does not ultimately serve the individual's self-interest.

Who is a better role model for a fulfilling life: Mr. Rogers or Genghis Khan?

It’s not just a philosophical question. There’s a scientific answer—one that might surprise some casual fans of evolutionary psychology, and some of its opponents as well. But the answer has practical implications for us as individuals, and as members of a broader society.

For years, some intellectuals raised objections to studying humans from an evolutionary perspective, fearing a close look at human nature would uncover a pit of Hobbesian brutish nastiness: “selfish genes” impelling us to emulate Genghis Khan—whose ruthless Y-chromosome was passed to 16 million modern descendants. But the latest scientific evidence, synthesizing findings from anthropology, biology, and psychology, argues otherwise: Someone in the modern world who wants a happy and fulfilling life is better off following in the kinder, gentler, footsteps of Mr. Rogers.

The Hobbesian view of human evolution gained some purchase outside academic circles. Newt Gingrich would recommend that newly elected Republican representatives read Franz deWaal’s Chimpanzee Politics: Power and Sex Among Apes. In Gingrich’s view, human leadership was a naturally bloody sport, with the goal of gaining power by any means, without compromise. Many everyday people read no further than the title of Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene to surmise that an evolutionary perspective implies self-centered individuals mindlessly driven to serve their selfish genes, in whatever way it takes.

This misconception has persisted for decades but is nevertheless a misconception—with two fatal problems. One is a philosophical mistake, the other a misreading of the actual data.

The Naturalistic Fallacy

The first problem with the “human evolution = selfish pursuit of power and sex” equation is the naturalistic fallacy—the mistaken idea that what is natural is good. Natural foods, flowers, birds, walks in the woods, what’s not to like?

But many natural things aren’t so “obviously” wholesome—parasitic wasps, AIDS viruses, and cancer cells are all perfectly natural, for example. Knowing some facet of human behavior is natural—in the sense of typical of our species and linked to past evolutionary success—does not imply it is morally good.

Males commit more homicides than do females across human societies, and across most vertebrate species. That tendency is linked to powerful evolutionary processes of sexual selection and differential parental investment. Natural? Probably. But good? Not for the victims, not for perpetrators spending life sentences behind bars, and not for society at large.

Scientific Data and Human Nature

The second problem is this: Alongside a few unpleasant inclinations, we also inherited powerful prosocial tendencies from our ancestors. It would be as accurate to say human beings are inherently cooperative as inherently violent.

Research examining a range of human societies indicates cooperativeness is a key feature of our species. Anthropologist Kim Hill and colleagues found that people living in small-scale societies, like those our ancestors inhabited, would not survive unless they shared food with neighbors. Other research, reviewed by anthropologist Richard Wrangham, suggests that selfish bullies—would-be Genghis Khans—are often excluded, attacked, and even assassinated by their neighbors.

Yearly fluctuations aside, violence is actually trending dramatically down since the time of Genghis Khan and our other, sometimes violent, ancestors. Life doesn’t seem peaceful if you read the daily news, because our natural attention to threats incentivizes the media to deliver a continual stream of threatening news. But for every person who committed homicide last year in the U.S., there were approximately 19,999 people who kept their inner Genghis Khan in check, and 11,199 who donated to charity.

Mr. Rogers Meets Evolutionary Psychology

In research our team conducted with collaborators in 27 other countries, we found that people’s primary motivations are not having lots of sexual partners and gaining power. Instead, people everywhere are more concerned with maintaining their long-term relationships and caring for family. Furthermore, individuals most concerned with taking care of their families feel less depression and anxiety, whereas those concerned with finding or changing romantic partners were relatively more depressed and anxious (Ko et al., 2020; Pick et al., 2022).

Elizabeth Dunn and colleagues conducted an experiment in which college students were handed $20 to spend either on themselves or on someone else. Observers predicted people’s moods would rise when reaping benefits themselves, but instead, people who spent the money on other people were happier afterward. Other research supports the idea that we are wired up to feel good when we make other people feel good.

A touching documentary about Fred Rogers suggests “Mr. Rogers” was the real thing—besides studying human development in graduate school, he was an ordained minister whose mission was to use TV to spread positivity to children—an antidote to violent cartoons and ads appealing to shallow materialism. His recurring message was to be good to your neighbors, but he wasn’t a naive Pollyanna. He talked with kids about anger, sadness, self-doubt, bullying, and even racial prejudice and assassination. But he also stressed that we had a choice—after confronting negative feelings, we could choose to act in a neighborly rather than a self-centered way.

What We Can Take Away

Modern research comparing people living in the modern urban world with people living in different societies and with other animal species suggests two take-home messages.

First, human nature ain’t all bad; there’s a healthy portion of kindness in there with any genes we inherited from Genghis Khan. Second, exercising our natural tendencies to act in unselfish and neighborly ways not only makes life better for those around us, and makes us feel good, it also increases the likelihood that others will help us in the future. So, ultimately, acting unselfishly is the best thing you can do for your selfish genes.

Coauthored by David Lundberg-Kenrick, who develops these arguments about positive evolutionary psychology more extensively in the book Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain.

References

Ko, A., Pick, C.M., Kwon, J.Y., Barlev, M., Krems, J.A., Varnum, M.E.W… (team of 34 international collaborators) & Kenrick, D.T. (2020). Family values: Rethinking the psychology of human social motivation. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15 (1), 173-201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691619872986

Kenrick, D.T., & Lundberg-Kenrick, D.E. (2022). Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain: Human evolution and the 7 Fundamental Motives. Washington: APA Books

Pick, C.M., Ko, A., Wormley, A.S., Wiezel, A., Kenrick, D.T. (team of 61 international collaborators)….. &Varnum, M.E.W. (2022). Family Still Matters: Human Social Motivation during a Global Pandemic. Evolution & Human Behavior, 43 (6), 527-535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2022.09.003

Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (2017). Ache life history: The ecology and demography of a foraging people. Routledge.