Serial Killers

Her Life Among Psychopaths

The first female FBI profiler reveals her experience with behavioral analysis.

Posted November 27, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- The first female profiler, Jana Monroe, shows what it took for women to advance in law enforcement.

- As a female member of the Behavioral Science Unit, Monroe offers her unique perspective on extreme offenders.

I’ve researched the history of behavioral profiling in the FBI and even before them, back to the 19th century. From surgeons to psychiatrists to magistrates to agents, those who’ve offered opinions about the kind of person who committed certain crimes have largely been male. Although Ann Burgess, a psychiatric nurse, collaborated on the development of the profiling program throughout the 1980s, she wasn’t an agent. Thus, Jana Monroe steps in to tell her story about being the first official female FBI profiler and the only female special agent in the Behavioral Science Unit (BSU) at the time.

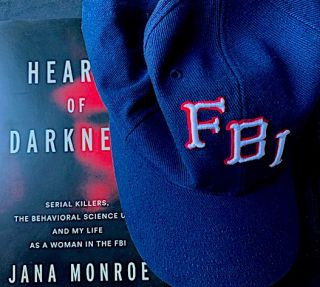

Entering the elite unit in 1990, she worked with the likes of John Douglas, Bill Hagmaier, and Roy Hazelwood. The workload was daunting: “During my five years in the unit, I was involved in roughly 850 cases.” Given how popular profiler books have been for the past several decades, it’s surprising that her life story, Hearts of Darkness, has only recently been offered. One might think it’s now outdated, but Monroe offers a narrative that is still relevant today. She takes readers back to a time when misogynist behavior was tolerated among cops and shows how important it was to actively resist it. As a pioneer in this arena, Monroe demonstrated impressive persistence.

She was reportedly the model for Jodie Foster’s portrayal of Clarice Starling in the film version of The Silence of the Lambs. In fact, she schooled Foster in “what it was like to be a woman in the male-driven and male-defined world of the FBI.” She also told the actress that approaching a nasty offender in a frame of mind that expects the worst is to miss opportunities where they tell the truth: “You’ve got to rid yourself of prejudice and any form of preconceived notion to do your job the right way.” A pivotal scene in the film was the interview that “Clarice” undertook alone with the monstrous and highly dangerous Hannibal Lecter. Monroe sets the record straight about what’s real and what’s improbable.

After describing the challenges of being a female police officer and then an FBI agent, she gets to some case details. Her recollection of the shocking rapes and murders of Joan Rogers and her two teenage daughters in Florida in 1989 displays the innovative thinking that moved Monroe upward through the ranks. With no apparent leads, the case went cold. The only clue they had was a handwritten note with directions to a causeway parking lot, where their abandoned car was located. Everyone assumed Joan had written it.

At the FBI, Monroe worked with Bill Hagmaier to write a profile for the likely offender (the text of which she provides). Monroe asked if anyone had compared the note to Joan’s or her daughters’ handwriting. No one had. When this was done, all three were eliminated as the author. Thus, they had a new lead, and the handwriting was distinctive. Monroe suggested enlarging it and placing it on billboards in the area. This move led to the identification of Oba Chandler, who was caught and convicted.

Monroe once got a call from the infamous “co-ed killer,” Ed Kemper, when she was working on a case in Philadelphia. He fancied himself an expert, but he seemed to project his own motivations onto the Unsub. His ideas, delivered in a monotone voice, left her shaken. Still, aside from Aileen Wuornos, she was not involved with most of the high-profile serial murder cases she mentions. For comments on them, she relies on the work of others.

The chapter on motivation is a highlight: “Why was what sustained us as we spent mind-numbing hours cozied up in prison interviews with murderous psychopaths.” Those of us in criminology and psychology want the details here. Monroe cites one piece of research published in 2020, which built off some of her work. It features an analysis of the motivations and behavior of 233 male serial killers with a known background of childhood abuse. She states that the study advances our understanding of serial killers far more than work done during the 1990s. For criminologists, pointing out this study is this book’s most valuable contribution.

“How to identify those very few [serial killers] headed that way before it was too late was our holy grail at the BSU. But hard as we tried, we could never pin down an exact ‘type’ that was more predisposed to serial murder than any other ‘types.’” Monroe came to recognize that a lot of people will do things that no one believed they’d ever do. Double lives are more common and more well-disguised than we think.

Monroe contends that what serial killers leave behind at the scenes and on victims (including living victims) tells a more honest version of their story than anything they might offer in a prison interview. Her journey is a revealing tour of our past in law enforcement, specific to females, and it also contributes an important part of the history of profiling that most other books on the subject neglect or ignore.

References

Marono, A. J., Reid, S., Yaksic, E., & Keatley, D. A. (2020). A behaviour sequence analysis of serial killers' lives: From childhood abuse to methods of murder. Psychiatry, Psychology, and Law: An Interdisciplinary Journal of the Australian and New Zealand Association of Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 27(1), 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/13218719.2019.1695517

Monroe, J. (2023). Hearts of Darkness: Serial killers, the Behavioral Science Unit, and my life as a woman in the FBI. Abrams Press.