Politics

Why Some People Turn Into Political Extremists

In the post-truth age, we will believe anything as long as it echoes us.

Posted August 25, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Wherever you fall on the political spectrum, chances are you have strong opinions on things that matter to you. You may also have a sense of loyalty and devotion to your political group, whether it’s a party, a movement, or a leader.

Politics is, and always has been, divisive. But with social media, things appear to be going from bad to worse.

In fact, a study conducted by the Pew Research Center revealed that over 50 percent of all American adults get their news from social media, which is notorious for creating echo chambers and propagating harmful misinformation. To add to the problem, research has shown that people who think they can’t be fooled by misinformation are the most likely to believe it.

This is the recipe for a post-truth-based society, where truth, fact, and objective reality are all relative to who you ask.

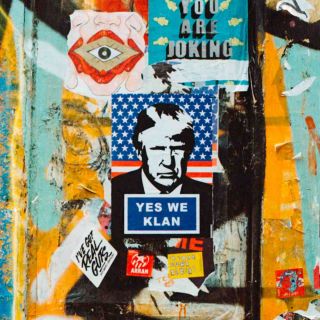

Let’s look at the rise of right-wing populism across the world today. Consider, for instance, how Germany is experiencing a neo-Nazi resurgence, Spain’s popular far-right political party Vox is at loggerheads with the LGBTQ community, and France’s far-right National Rally party, led by Marine Le Pen (who is vehemently anti-immigration in her beliefs), is gaining more support from voters. America, too, finds itself entrenched in an uncertain, hyper-polarized society where many people who supported Donald Trump throughout his presidency continue to do so.

With this as context, here are the two questions every engaged citizen should ask themselves:

- Have the concepts of “my truth” and “your truth” caused irreversible damage to our ability to be objective in our political leanings?

- Is it possible to have polarized views on political issues and, as a society, still get along?

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers. But there is one crucial piece of information that can help us understand why political extremists sometimes cling to wild beliefs despite evidence to the contrary. It has to do, at least in part, with the need to belong.

Virtue Signaling May Explain The Spread of Misinformation Among Political Extremists

A recent study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General explored, through a series of three experiments, how conservatives in Spain and the United States respond to misinformation that aligns with their political values.

In the first experiment, conservatives from Spain who were either far-right or center-right were shown various social media posts criticizing the liberal government. These posts were designed to either appeal to their conservative sacred values or their non-sacred values. Sacred values are moral imperatives that people are unwilling to compromise while non-sacred values can be weighed against other values and may be subject to negotiation or trade-offs.

The experiment showed that despite fact-checks and accuracy nudges (like you would see on popular social media platforms like Twitter or Instagram), far-right individuals were far more likely compared to center-right individuals to reshare blatant misinformation. This was especially true if the post resonated with their sacred values and if their personal identity was closely related to their political ideology.

For the second experiment, the researchers replicated the social media experiment in the United States, where they found similar results among Trump-supporting Republicans. In fact, Republicans who voted for Trump (and self-identified as Trump supporters) were found to be undeterred by Twitter fact-checks and were willing to share the misinformation anyway. This tells us that social media fact-checks or flagging of “fake news” may not sufficiently prevent the spread of misinformation, especially when it has an extremist agenda attached to it.

To understand the brain activity of political extremists viewing misinformation, the researchers conducted a third experiment on 36 participants from Spain who supported the far-right political party, Vox. Here, the researchers repeated the same procedure as in the first and second experiments, but this time they conducted an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) to observe the changes in participants’ brains as they were asked to decide if they would reshare the social media post.

The experiment revealed that certain parts of the brain, like the bilateral inferior frontal cortex and the precuneus, were more active in these individuals when they contemplated sharing the post. These areas of the brain are involved in making you feel like you belong to a social group, understanding other people’s emotional states, and responding to social cues in ways that are considered socially appropriate.

Plainly speaking, when these far-right individuals choose to share misinformation, they are likely doing so because they view it as a way to signal to other like-minded extremists that they belong to the same social and political group. This need to virtue signal is the strongest when the misinformation presented to them is related to values that are considered sacred to their community, which, in the case of the far-right, may involve issues such as immigration, religion, or nationalism.

Conclusion

Understanding the emotional and societal factors behind misinformation spread is key. The issue isn’t just about debunking false information—it also involves addressing extremists’ need for social belonging and identity affirmation. In a world divided by “my truth” and “your truth,” striving for critical media literacy and open dialogue can build bridges and potentially free us from the prison of our beliefs.