Psychology

Resistance to Change and the Wisdom of Buddhist Psychology

Fighting against natural and inevitable change is a prescription for suffering.

Posted September 28, 2021 Reviewed by Ekua Hagan

Key points

- Life itself is an ongoing progression of growth and change that involuntarily takes people from one phase or stage of development to another.

- Growth cannot occur without loss, and fighting against the inevitable losses that happen as life progresses creates unnecessary suffering.

- In spite of the universal truth of ongoing change, there is a natural human desire to expect things and people to remain the same.

- Trying to hold onto things—or people—as they were is a futile struggle, akin to attempting to keep the tide from coming in.

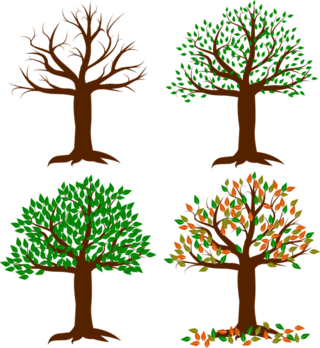

Many people struggle with and even fight (mentally and emotionally) against the ongoing process of change that human beings naturally and ineluctably experience throughout our lives. Life itself is an ongoing progression of growth and change that takes people from one phase or stages of development to another—from infancy to older age. Not surprisingly, we very much prefer some stages to others and may try to desperately hold onto them (or cling fervently to the memories of them), while striving to push other stages away in the wish to deny, avoid, or minimize these.

Gains and losses occur with each successive developmental stage. In fact, growth cannot exist without loss; like a snake shedding its outgrown skin, people grow beyond what no longer fits them. This dynamic also characterizes the process of recovery from addiction, as well as any process of significant life change that involves progressive learning and growth.

Separation-individuation

Related to parenting, our children’s need to grow their own wings becomes obvious during adolescence with the process of separation-individuation and continues to manifest in young adulthood. Separation-individuation, wherein kids more assertively start to develop their own identities as individuals separate from their parents, is a natural and essential part of healthy psychological development. It is part of the circle of life in action.

Yet, many parents struggle with their children’s separation-individuation. Their love for their children may be undiminished, but rather than emotionally supporting their kids as they sprout wings and desire greater distance and increasing autonomy, often, consciously and unconsciously, they discourage it. As one unfortunate example, I’ve seen deeply caring, otherwise incredibly supportive parents encourage their kids to attend college locally rather than go away for school, and live at home rather than on campus (unrelated to financial issues)—sometimes promising to buy them a car as part of the deal—in order to keep them close.

While it’s normal, understandable, and healthy for parents to feel ambivalent and sad as their children advance toward adulthood, they need to work through such emotions, separating their needs from those of their children (as hard as it may be). Parents who cannot adjust to and accept these losses do their children a great disservice.

Kids pick up on these feelings and can become consciously and unconsciously influenced by them, sometimes finding ways to clip their own wings to assuage their parents’ discomfort. Whenever parents are unable to deal with the losses inherent in their children’s natural progression toward independence and a life of their own choosing, the development of healthy wings is inhibited.

Attachment and impermanence

One of the immutable realities of the universe is that everything changes all the time. Over time, our relationships, our communities, our bodies, our health, our worldviews, and our children, along with the relationship we have with our children, all change. In spite of this universal truth, we continue to expect things and people to remain the same.

This is reflected in the first law of Buddhist psychology: All phenomena are impermanent and constantly changing, yet we tend to relate to them as though they were permanent. Trying to hold onto things, or people, as they were is a futile struggle, akin to attempting to keep the tide from coming in. It is a denial of reality that generates tremendous stress and unnecessary suffering.

As the second of Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths informs us, the attachment to and desire for something different from the reality of “what is” causes and exacerbates suffering. When parents cling to images and recollections of their children as they were in earlier developmental stages, rather than respect the needs and interests of their children as they evolve, they create suffering for themselves and their children. And the more parents resist their children’s growth and put more effort into fighting against and denying age-appropriate changes, the more suffering they create.

This leads to another loss for parents: the opportunity to appreciate their kids as they are in each precious developmental stage, remembering that it will never come again. As Tibetan Buddhist master and teacher Anyen Rinpoche put it, “If we’re not reflecting on the impermanent nature of life ... a lot of unimportant things then seem important.”[1]

Copyright 2021 Dan Mager, MSW

References

Anyen Rinpoche and Allison Choying Zangmo, Living and Dying with Confidence: A Day-by-Day Guide (Massachusetts: Wisdom Publications, 2016).