Gaslighting

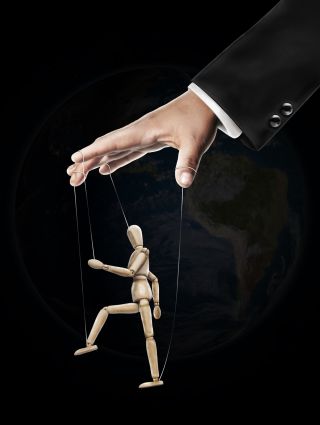

What Exactly Is Gaslighting, and Why Do People Do It?

A new study shows what drives people to gaslight and how to recover from it.

Updated August 14, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- New research sheds important light on the motivations, effects, and dynamics of gaslighting.

- Gaslighters are primarily motivated by avoidance of accountability and the desire to control others.

- Gaslighting is a process that unfolds across multiple stages and impairs trust in both oneself and others.

- Recovery and post-traumatic growth are possible after being gaslighted.

During the last several years, it’s been impossible to avoid the term “gaslighting.” In fact, it was selected as Merriam-Webster’s 2022 Word of the Year based on the frequency of searches for it. But what does it mean, really?

Merriam-Webster defines gaslighting as “psychological manipulation of a person usually over an extended period of time that causes the victim to question the validity of their own thoughts, perception of reality, or memories and typically leads to confusion, loss of confidence and self-esteem, uncertainty of one’s emotional or mental stability, and a dependency on the perpetrator.”

The word originates from the 1938 play Gaslight by Patrick Hamilton, in which a husband tries to convince his wife she’s losing her mind to distract her from his criminal behavior. Considerably more recently, the internet accused a Bachelor contestant of gaslighting a date related to a disagreement over their interactions on that show.

However, in spite of its increasing attention in the media and prominence in pop culture, scientific research on gaslighting has been surprisingly limited. A new study published in the journal Personal Relationships changes that, focusing on the effects of gaslighting in romantic relationships. The study also identifies the underlying motivations of gaslighters, as well as how gaslighting unfolds within relationships.

Through a qualitative analysis of survey responses from 65 gaslighting victims (ages 18 to 69), researchers from McGill University and the University of Toronto describe a number of traits and behaviors gaslighters generally share. [1]

Gaslighters are motivated primarily by two things

- To avoid accountability for their own bad behavior.

- To control the victim’s behavior.

*It’s important to note that the researchers only interviewed survivors of gaslighting, relying on their interpretation of the abuser’s motivations. It seems entirely reasonable to assume that those accused of gaslighting—an inherently disingenuous behavior—would deliberately be less than honest about their motivations and perhaps even attempt to gaslight the reseachers.

One major theme that emerged was gaslighting as an attempt to avoid accountability, most often for infidelity-related actions. The second motivation was a more general desire to control the survivor, to dictate how they behaved, who they had contact with, what they wore, etc.

Gaslighting unfolds across multiple stages

Study results indicate that four behavioral patterns were common in gaslighting relationships:

- “Love-bombing”—an excessive shower of attention, which usually occurs at the start of a relationship

- Progressively separating or isolating the victim from friends and family

- Perpetrator unpredictability—the gaslighter unpredictably changes their behavior, often from one emotional extreme to another

- Cold-shouldering—withholding or withdrawing affection and communication.

Love bombing is a tactic that involves overwhelming someone with excessive displays of attention and affection with the intent to manipulate them. The experience of seemingly having one’s emotional needs fulfilled so quickly creates an intense emotional bond and even a sense of indebtedness to the gaslighter, giving them power and control.

This rapid and intense emotional connection significantly accelerates the process of creating epistemic trust, giving the gaslighter greater influence over their partner’s beliefs, including beliefs about themself. Epistemic trust is an essential part of healthy relationships in that we need to be able to rely on our partners to validate and expand our beliefs about ourselves. Under most circumstances, it is built gradually over the course of time and experience. Gaslighting intentionally abuses this trust.

The primary effects of gaslighting

The researchers identified three notable adverse effects on people who’d been gaslit:

- A diminished sense of self with increased uncertainty

- Increased guardedness

- Increased mistrust of others

In direct contrast, healthy relationships generally reduce one’s feelings of uncertainty, expand the sense of self, and create a sense of shared reality. Gaslighting destroys any semblance of a sense of shared reality and seeks to create two separate, effectively competing realities and convince the victim that only the perpetrator’s version is valid.

The most classic example is directly calling someone “crazy” and outright dismissing their perception of reality. Other common insults used by gaslighters include “stupid,” “irrational,” or “needy.” The gaslighter gets their partner to question their perceptions and uses this uncertainty to undermine their judgment and boundaries as a way of controlling them.

While most victims of gaslighting in the study recovered relatively quickly after separating from their gaslighter, a few felt enduring uncertainty and remained unsure of themselves, according to the researchers. The experience of being gaslit has the potential to alter one’s views on other social interactions, affecting the ability to trust and leading to greater vigilance and being on guard with others.

Recovery and post-traumatic growth are possible after being gaslit

For those participants who reported some degree of recovery, certain themes emerged. For many, ending the relationship with the perpetrator and spending time with others brought rapid relief from the negative effects of gaslighting. Beyond spending time with others, engaging in re-embodying activities—such as yoga, meditation, Qi Gong, hiking, and sports—that lead to a greater sense of connection with one’s physical self and expand opportunities for introspection helped to facilitate healing.

If you ever have the sense that you are being gaslit, it’s beneficial to involve other people and to seek the feedback of trusted others. If a partner is telling you that you’re acting irrationally about something, reach out to friends or family and ask them if they’ve noticed the behavior the abuser is criticizing. Getting feedback outside the relationship is essential because gaslighting can be effective in causing people to doubt their own perceptions and actions.

The most important positive takeaway from this new research is that it is absolutely possible to move on and grow beyond the experience to build healthier relationships after being involved with a gaslighter.

Copyright 2023 Dan Mager, MSW

References

[1] Klein, W., Li, S., & Wood, S. (2023). A qualitative analysis of gaslighting in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 1– 25. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12510