Coronavirus Disease 2019

Should People Be Able to Choose Which Vaccine They Receive?

The ethical and practical case for offering the public a choice of vaccines.

Posted February 26, 2021 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key Points:

- As more vaccine formulations become available, it may be possible to allow patients to choose which vaccine they'd prefer.

- Research suggests that allowing vaccine choice could help bolster the immunization effort by increasing patient autonomy and engagement.

- However, constantly changing information about vaccines could confuse patients trying to make a decision, and logistical factors could force some clinics to limit choices.

- Policymakers should aim to frame the choice in a straightforward manner and focus on factors (side effects, effectiveness, etc) that consumers care about most.

Imagine that you are on Yelp searching for a gutter cleaning service before winter rains arrive. In your query, you find two companies with dozens of customer reviews and nearly 5-star averages. There are a couple of others with just a handful of middling reviews and one carries the unfortunate tag “Gutters will be clean, sort of.” It looks like all will cost about the same, but oddly, the high-ranked ones will require two separate visits to the home. Of course, the weather being what it is, you really don’t know when it might rain and how much. So, what should you do—wait for the best or get the job done ASAP?

Well, hold that thought—because this post isn’t about gutters but rather informed choice and whether it has a role to play in the next phase of COVID vaccine distribution. To answer the question of whether people should be allowed to pick and choose which vaccine products they would accept, the discussion begins with informed consent and its underlying bioethical pillar, patient autonomy.

“Every human being of adult years and sound mind has a right to determine what shall be done with his own body," so written by Justice Benjamin Cardozo in 1914 in articulating the concept of autonomy. It wasn’t until the last half-century, however, that this basic principle was widely accepted and implemented. Before then, there existed a pervasive notion that doctors were best equipped to make decisions about what information was healthy for their patients and what was not—just as a parent would do with diet choices for a young child.

The transformation from a paternalistic, “we know what is best” approach to an autonomous approach was spurred not just by the words of Justice Cardozo, but also by revelations about unethical medical studies, including the “research” atrocities committed in Nazi Germany and the infamous Tuskegee (Alabama) syphilis studies. These cruelties made the critical weakness of paternalistic medicine—the potential for abuse in the name of another’s best interests—unmistakable and unacceptable. Nowadays, a competent patient cannot receive a medical intervention or participate in a research trial without autonomously giving “informed consent.”

Informed consent is one thing, but what about informed multiple choice in the setting of a pandemic in which the over-whelming public health imperative is attaining herd immunity as quickly as possible? Up until now, this discussion hasn’t been needed in the U.S.—the arrival of vaccines was so welcome for most recipients that there wasn’t much deliberation in attempting to choose between the two available products. Of course, it has also helped that the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines are very similar, both in how they work and how effective they are. Now, however, as we slowly plow through the highest risk tiers and phases towards opening vaccination to a large swath of the public, it seems likely that there will be more vaccines in the mix in the very near future and that they will have distinct characteristics.

To help sort out what the pending approval of the Johnson and Johnson and perhaps other options means for those still waiting for their vaccine, I spoke with bioethicist Arthur Caplan. Caplan is the Drs. William F. and Virginia Connolly Mitty Professor of Bioethics at New York University Langone Medical Center and the founding director of their Division of Medical Ethics. He has had much to say about the bioethical challenges of COVID-19. We discussed what would seem to be three of the most important questions on the topic of vaccine choice.

Q: Should we offer the public a choice of vaccines?

Up until this point, Caplan said, the answer has been “no” due to the remarkable equivalence of the two choices. “I didn’t care which one I received,” he told me. “There was very little reason to wait for one or the other.” (As a frontline provider myself, I would absolutely second that notion—no matter what approved product I received in December, my initial reaction would have been the same: euphoria!) However, with new approvals on the immediate horizon and the likely need for booster shots later in 2021, an ethical mandate to provide a choice may be evolving.

“Every provider,” Caplan foresees “will need be prepared to discuss choice as well as vaccine hesitancy. These are adults we are talking about, not kids, and it is going to be important to think about a choice paradigm that includes the do not want choice.” This discussion is likely to become more nuanced for some workers (e.g, those in the military or cruise industry) who may soon be mandated to receive a vaccine. Caplan expects this to happen as soon as this summer and the do not want choice is likely to have employment ramifications.

Q: Could offering vaccine choice help immunization efforts?

“Yes” says Caplan. There is some evidence from other settings that providing choice can engage the patient in their own medical decision-making and may improve compliance. Using a choice-based approach might also take advantage of a vaccine market that is polarized—many people in lower priority tiers are desperate to get vaccinated while others in high-risk groups are more hesitant. Incorporating a choice-based component to vaccine allocation may take advantage of a sector of the market that is willing to get the job done ASAP and help further the broader imperative, which is community-wide immunity.

There are potential downsides, however. These include the fluid nature of evidence with regard to vaccine attributes. One week we are told that one shot of Pfizer is 50 percent effective; the next we learn it is more like 90 percent. And there will be supply chain and logistical considerations that may make the choice a regional consideration. Rural areas with tenuous supply chains may opt to put all of their vaccine vials into a one-shot and done basket, limiting choice for those not willing or able to travel longer distances.

Q: If such a choice is to be made, how should it be framed?

This is tricky, Caplan explains. First, we know that people’s understanding of the information given to them during the informed consent process is seldom fully understood or retained. For example, a survey of people involved in a clinical trial of a cholesterol-lowering medication found that only 31 percent could name the main side effect of the treatment. How informed is your consent if you don’t know what side effects to look out for?

Along these lines, it can be easy to overwhelm with consent-related information (a “truth dump” Caplan calls it), to the point that people make poor decisions as their over-stimulated neurons scream at them to “simplify!” Fortunately, in this situation, we do have some existing evidence to guide us as to what details are important in the vaccine choice decision.

Even before Moderna and Pfizer achieved emergency use authorization, researchers were already thinking about this. Two survey studies from last summer (Kreps, Dong) used techniques developed in market research to assess what information would most impact a person’s decision to receive a particular vaccine.

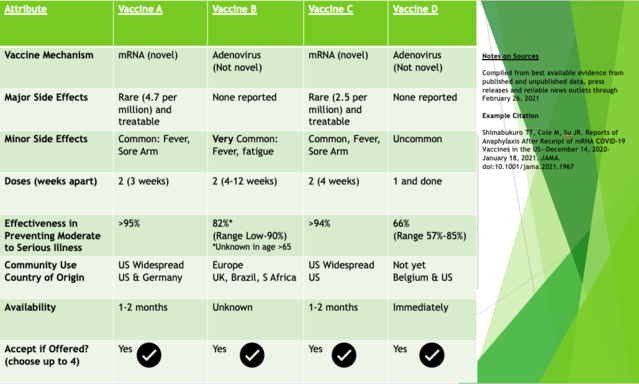

For example, the survey study of 1,971 U.S. adults found the following attributes were most important in vaccine decisions: their effectiveness, severe side effects (as opposed to mild ones), and duration of immunity. (Kreps) A Chinese study had similar findings with the exception that respondents also had a preference for an overseas product compared to one made at home (it would seem that Buy Domestic is not so resonant in China). (Dong) Based on this work and existing data as of February 2021, an informed multiple-choice tool might look something like this:

One might envision people encountering such a tool as they register expressing their interest in receiving a vaccine (in California this is done via the website MyTurn) and consider the trade-off of priorities that might cause them to choose first available at the moment or wait for the top reviewed options. If, or rather when, we get to the booster shot phase of this pandemic, vaccine choice may look much different as vaccine distribution becomes less strictly funneled and pharmaceutical companies market their product directly to the public.

So, if you have made it this far, you may not have clarity on what to do with your gutters. But, if the choice hasn’t already been made for you, maybe it has given you some substrate for making your own informed vaccine decision.

References

Kreps S, Prasad S, Brownstein JS, Hswen Y, Garibaldi BT, Zhang B, Kriner DL. Factors Associated With US Adults' Likelihood of Accepting COVID-19 Vaccination. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Oct 1;3(10):e2025594. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.25594. Erratum in: JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Nov 2;3(11):e2030649. PMID: 33079199; PMCID: PMC7576409.

Dong D, Xu RH, Wong EL, Hung CT, Feng D, Feng Z, Yeoh EK, Wong SY. Public preference for COVID-19 vaccines in China: A discrete choice experiment. Health Expect. 2020 Dec;23(6):1543-1578. doi: 10.1111/hex.13140. Epub 2020 Oct 6. PMID: 33022806; PMCID: PMC7752198.