Empathy

Empathic People Use Social Brain Circuitry to Process Music

High-empathy people process music using their social cognitive circuitry.

Posted June 18, 2018

Those who deeply grasp the pain or joy of other people and display “higher empathic concern” process music differently in their brains, according to a new study by researchers at Southern Methodist University and UCLA. Their paper, “Neurophysiological Effects of Trait Empathy in Music Listening,” was recently published in the journal Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience.

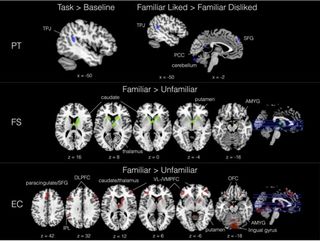

As you can see by looking at the images at the top of the page and to the left, the SMU-UCLA researchers used fMRI neuroimaging to pinpoint specific brain areas that light up when people with varying degrees of trait empathy listen to music. Notably, the researchers found that higher empathy people process music as if it’s a pleasurable proxy for real-world human encounters and show greater involvement of brain regions associated with reward systems and social cognitive circuitry.

In the field of music psychology, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that varying degrees of trait empathy are linked to how intensely someone responds emotionally to music, his or her listening style, and overall musical preferences.

For example, recent studies have found that high-empathy people are more likely to enjoy "beautiful but sad" music. Additionally, high empathizers seem to get more intense pleasure from listening to music in general, as indicated by robust activation of their reward system in the fMRI.

The latest research on the empathy-music connection was conceived, designed, and led by Zachary Wallmark, who is a musicologist and assistant professor in the SMU Meadows School of the Arts. In 2014, Wallmark received his PhD from UCLA. He currently serves as director of the MuSci Lab, which is an interdisciplinary research collective and lab facility dedicated to the empirical study of music. Below is a YouTube clip of Wallmark describing his latest research:

"High-empathy and low-empathy people share a lot in common when listening to music, including roughly equivalent involvement in the regions of the brain related to auditory, emotion, and sensory-motor processing," Wallmark said in a statement.

But, there are some notable differences in how trait empathy influences music listening. In a side-by-side analysis, Wallmark's team found that highly empathic people process familiar music that they “like” and “dislike” with greater involvement of the brain's social circuitry in comparison to their less empathic peers. These are the same neural networks that are activated when someone feels empathy for another person in real-world situations.

"This may indicate that music is being perceived weakly as a kind of social entity, as an imagined or virtual human presence," Wallmark said. “This study contributes to a growing body of evidence that music processing may piggyback upon cognitive mechanisms that originally evolved to facilitate social interaction."

According to the researchers, this SMU-UCLA study is the first to unearth empirical evidence supporting a neurophysioplogical representation of the music-empathy connection. Also, this is pioneering research in terms of using state-of-the-art fMRI neuroimaging to investigate how empathy affects the way different people perceive music.

Although many people view music simply as a form of artistic expression or entertainment, Wallmark et al. posit that music is a universal language that may have evolved to help humans interact, communicate, and understand one another.

"If music was not related to how we process the social world, then we likely would have seen no significant difference in the brain activation between high-empathy and low-empathy people," Wallmark said. "This tells us that over and above appreciating music as high art, music is about humans interacting with other humans and trying to understand and communicate with each other.”

"But in our culture we have a whole elaborate system of music education and music thinking that treats music as a sort of disembodied object of aesthetic contemplation," Wallmark said. "In contrast, the results of our study help explain how music connects us to others. This could have implications for how we understand the function of music in our world, and possibly in our evolutionary past."

"The study shows on one hand the power of empathy in modulating music perception, a phenomenon that reminds us of the original roots of the concept of empathy — 'feeling into' a piece of art," senior author Marco Iacoboni, a neuroscientist at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, said in a statement. "On the other hand, the study shows the power of music in triggering the same complex social processes at work in the brain that are at play during human social interactions."

After reading about this study, I was curious to learn more about Zachary Wallmark's research. Below is the summary of a correspondence (edited for clarity) that I had with Zachary ("ZW") via email and over the phone.

Conversational Q&A with Zachary Wallmark and Christopher Bergland

CB: Zach, thanks for taking the time to share some more details about your latest research on the empathy-music connection. In addition to the succinct description of your latest study in the YouTube clip shared earlier in this post: Is there anything significant or surprising about your latest fMRI study on the differences between high-empathy and low-empathy music listeners that you’d like to emphasize for the general Psychology Today reader?

ZW: Thank you for inviting me, Christopher. As everybody knows, music is a window into others’ feelings and intentions. It also conveys a lot of social information. When you first hear a song, you’re probably immediately asking yourself whether or not you like it. You’re also hearing it through an explicitly social lens. Who is this singer? What is she trying to express? Is she like me, or different? It’s hard to imagine music listening without the explicit assessment of others’ minds.

Our results are significant in demonstrating a link between trait empathy in the social domain and neural processing in the musical domain. This finding suggests that individual social cognitive differences are correlated with functional differences in the brain when processing music. Given that music isn’t an explicitly social stimulus the way that, say, a smiling face or a conversation with a co-worker are, this is a somewhat surprising result. It tells us that a tendency toward empathic connection with others bleeds over into how people make sense of music. The two processes share common neural circuitry.

Another particularly surprising finding was that high-empathy people showed more reward system activation even when listening to music that they self-selected as “strongly disliking.” This counterintuitive result suggests to us that the familiarity effect in musical preference—sometimes referred to as the “mere exposure” effect—is more pronounced among empathic people. From a social perspective, this association makes some sense: if you’re the type of person who tries to “see something positive” in others, you might do the same with music, even the music you have a strong aversion to.

Related to this, we also found that high-empathy people showed greater involvement of dorsolateral prefrontal areas when listening to unfamiliar/disliked music. This area is closely associated with executive control and emotional regulation. Interpreted through the framework of empathy differences, this could indicate that empathic listeners worked a little harder to down-regulate negative reactions to the unfamiliar music, trying to give the benefit of the doubt to new music that they nevertheless rated poorly after the scan.

CB: Earlier this year, a Harvard University study "Form and Function in Human Song," (Mehr et al.) reported that lullabies and dance songs stand out as universally identifiable forms of song that are used to 'soothe a baby' and 'move one's body in synchrony to a rhythmic beat' respectively. (For more see, "Dance Songs Dissolve Differences That Divide Us.")

Along this same line, in March 2018, Molly Henry of the Brain and Mind Institute at the University of Western Ontario, gave a presentation, “Live Music Increases Intersubject Synchronization of Audience Members’ Brain Rhythms,” at the 25th annual meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society in Boston.

Based on your research and the findings of others in your field, do you think that encouraging people to go out dancing more regularly and to attend live musical performances could be an underutilized prescriptive "fix" to help mend the fabric of our society that seems increasingly frayed by various factors associated with 21st-century, modern-day living?

ZW: This is an intriguing possibility. The use of music for dancing and group physical coordination has to be one of the oldest and most widespread uses of music in human cultures. Aside from the personal physical pleasures of rhythmic synchronization (what psychologists call entrainment), orchestrating movement together in a group may have a number of conceivable personal and collective benefits. The discipline of music therapy has convincingly shown that music can indeed be used to help ameliorate a number of physical and mental ailments, including stress, anxiety, motor control disorders, language disorders such as aphasia, as well as certain social impairments. (And, of course, it doesn’t take a licensed therapist for us to “self-medicate” with music, whether to calm the nerves, get us pumped up for a night out, be a friend when we’re experiencing loss, or any other conceivable use.)

However, from a social perspective, we should keep in mind that music can exclude just as much as it can bring people together. It’s not a panacea. Often we signal our distastes in music just as strongly as we show our tastes, sometimes to demonstrate what kind of person we think we are (in implicit contrast to “those people”). In this regard, I feel like the truest potential for music to function as a kind of “social fix” would be for us to deliberately seek out unfamiliar music that’s associated with groups of people we might not immediately identify with. It may seem alienating at first, like the music isn’t meant for you and you’re eavesdropping, but I think it might help us expand our circle of empathy toward others. For example, parents could make a concerted effort to listen to and try to understand their teenager’s electronic dance music; conversely, teenagers could connect with grandma by listening open-heartedly and maybe even trying to dance to the big band swing hits of the ‘40s.

CB: As a gay teen in the early 1980s, I suffered from a major depressive episode (MDE) that included suicidal ideation, substance abuse, and crippling perceived social isolation. At the time, Pink Floyd's rock opera, "The Wall" was at the top of the Billboard charts. I listened to this double album and the singles "Another Brick in the Wall" and "Comfortably Numb" incessantly.

The video imagery from Alan Parker's 1982 film adaptation got deeply etched into my "theory of mind" mechanisms. Putting myself in the shoes of the central protagonist of "The Wall" storyline on a daily basis wasn't necessarily good for my mental health. Although I still derive intense pleasure from listening to their ‘classic rock’ as an adult, in many ways, Pink Floyd's music exacerbated my hopelessness and self-destructive tendencies as a teenager.

Fortuitously, in 1983, I went to see Madonna perform in a small nightclub before she was famous. Her gutsy self-expression, laid-back perfectionism, and joie de vivre were contagious. To this day, the song "Holiday" never fails to help me "let love shine" and wish that we could "come together, in every nation" without being a Pollyanna.

Madonna was the first performer I'd ever seen in concert who didn't seem to care about audience members' sexual orientation. Watching her live and listening to her first album on a cassette in my Walkman was the catalyst that inspired me to start jogging and stop doing drugs.

The combination of blasting Madonna music in my headphones while working out really hard seemed to rewire my neural circuitry and gave me the courage to come out of the closet. As a role model, Madonna's lifestyle and music videos (e.g., "Borderline," "Express Yourself," "Into the Groove") showed me how to be more extroverted and open to new experiences in my day-to-day life. I'm not ashamed to admit that like millions of teenagers (mostly girls) in the mid-1980s, I was a "Madonna Wannabe" on a psychological level.

In the book acknowledgments for The Athlete's Way: Sweat and the Biology of Bliss, I express my lifelong gratitude to the Queen of Pop: "Thank you [Madonna] for laying the brain chips of excellence and fearlessness in my head when I was seventeen and for being rocket fuel during every workout ever since."

Anecdotally, there are countless examples of musical performers having a potent impact on the individual and collective consciousness of their fans. Does your research provide any empirical evidence that the musical performers we adore and listen to frequently can shape the worldview or behavioral tendencies of their fan base on a neurophysiological level?

ZW: This is an important question in the psychology of music. It’s also probably the oldest: Plato talked about the power of certain kinds of music to influence behavior and outlook, even going as far in The Republic to propose that some music should be banned due to its potent effects. From the perspective of modern neuroscience, we now understand clearly that musical training and exposure can alter the physical structure of the brain.

As you noted in the last question, moreover, music can synchronize many individuals through mechanisms of rhythmic entrainment. This can provide people a sense of social harmonization and bonding. To be sure, there are numerous documented cognitive, sensory-motor, emotional, and social benefits to musical engagement, and musicians have clearly understood this for as long as humans have possessed music (that is, since the beginning of our species!).

There are a number of challenges associated with establishing a causal relationship between musical engagement and worldview/behavior. Our study (and many others using neuroimaging) explores correlations, not causations. However, when different behaviors interrelate, we can sometimes infer that they share an underlying structure or tendency. In this case, it would seem that two seemingly unrelated processes—empathy and music listening—may be related in terms of neural representation. Since empathy typically encompasses both a worldview and a basket of associated prosocial behaviors, it would seem that music, while not necessarily always “shaping” personality and perspectives directly, is capable of powerfully reinforcing these tendencies.

CB: As the father of a 10-year-old who was born in 2007, I try to encourage my daughter to listen to popular music that promotes loving-kindness and empathy. Of course, she's old enough to self-select musical artists and genres that she inherently likes or dislikes. To my ears, so much of today's popular music has a soul-less, computer-generated feeling and I can't find much "there, there." That being said, I know that some of your research focuses specifically on popular music in America after World War II (1946) and the influence of music in society over the past seventy years.

Through the lens of generational differences from the mid-20th century to current modern-day living: "Exhibit A" of popular music and society in early post-WW II America could be my mom and dad, who were teenagers in the 1950s. A decade later, both of my parents strongly identified with the 'love-peace-and-harmony' empathic "Woodstock" music of the 1960s.

I was born in 1966, a year before the “summer of love.” During my childhood, the singer-songwriter music of Jackson Browne, Kris Kristofferson, John Denver, James Taylor, Carole King, Carly Simon, Joni Mitchell, etc. was always in heavy rotation on the turntable in the family den or playing on the 8-track in our wood-paneled station wagon. This folksy, “self-reflective” genre of music was also omnipresent on Top 40 radio in the early- to mid-1970s. I have a gut instinct that listening to this music nonstop during my youth may have laid down scaffolding in my brain that makes me respond more emotionally to familiar and unfamiliar popular music.

As a real-time example, this morning, I headed out for a long jog in the predawn hours with a playlist of nostalgic music from my youth cued up on my smartphone. Just as the sun was coming up over the horizon, the song "Morning Has Broken" by Cat Stevens randomly started playing on shuffle mode.

I know this is cliché. But, the cinematic moment of watching the sunrise while hearing this song opened up a memory box that gave me vivid flashbacks to how I viewed the world as a 10-year-old back in 1976. Because I rarely listen to this song, it felt like the exact neural circuitry associated with this classic Cat Stevens' tune had been preserved like a time capsule from my preadolescence. Tapping into the innocence and spiritually-based compassion for "all living things" held in this song made me verklempt and seemed to wash away some of the cynicism and vitriol the current sociopolitical climate triggers whenever I catch a glimpse of cable news.

Along this line, in May 2018, researchers from the Center for Healthy Minds in Madison, Wisconsin reported that compassion is like a muscle that gets stronger with training. Do you know of any science-based reason to believe that listening to music that promotes loving-kindness, compassion, and empathy can influence someone's neural circuitry in ways that would make him or her more empathic in real-world situations?

ZW: A beautiful recent study out of Oxford (Vuoskoski, Clarke, & DeNora, 2016) explored a similar question. Using an implicit association task, the researchers reported that exposure to music from unfamiliar cultures could increase implicit preference for members of that cultural group among high-empathy participants. This wasn’t a brain imaging study, but the implication seems clear: music modulated empathic response in real-world social evaluation for those who were dispositionally empathic. There is bountiful historical evidence of this kind of phenomenon as well. For example, music played a pivotal role in the emancipation movement of the 19th century: the more positive exposure white Americans got to African-American music, the more sympathy and concern they expressed toward this marginalized group.

Now, in light of the Oxford study, we might ask ourselves how much of this effect was due to the music alone, and how much represents a complex interaction between musical exposure and personal, socio-cultural, and historical variables. Nonetheless, the correlation is revealing. This pattern of music helping to humanize other groups is widespread today, and the history of American popular music is, in many ways, the unfolding of this general idea.

I sure resonate with your experience of being suddenly transported back in time by a song. This last weekend I took a road trip with my wife and 5-year-old son, and we played the original London recording of Jesus Christ Superstar as we zoomed through rural Oklahoma. This was our go-to road trip music when I was a kid: it was powerful to replay this soundtrack in memory as a new memory was being forged in my son. He may do the same thing when he’s a father. This kind of inter-generational experience of music can be immensely powerful and enduring. It’s also a deeply social experience: Is it really possible to look back on your own listening life without invoking the people around you at that stage? Even examining memories of a previous version of yourself is a social cognitive task: your past self is often experienced as both “you” and “not you,” and it’s common for people to imagine their past selves from a third-person perspective.

Empirical research into music-evoked emotion has exploded in recent years, and autobiographical association has emerged as one of the key mechanisms driving emotional reactions to music (Juslin & Västfjall, 2008). This kind of experience also appears to have a unique neurophysiological signature (Janata, 2009). The role of nostalgia in musical preference is not yet well understood, and clearly deserves more study.

CB: One aspect of your latest study involved having individual participants self-identify familiar songs they either "loved" or "strongly disliked" prior to having a brain scan to test responses to various types of music in the fMRI. After learning about this study design, I was inspired to keep my ears open for popular music that evokes what feels like a strong neurophysiological response in my brain. For example, after reading about your study I used the "Shazam" app to earmark eight random songs I heard on the radio that I either 'loved" or "strongly disliked."

Four popular songs I heard on the radio this weekend that I really liked were: “Getting Ready to Get Down,” “Snapback,” “Dreamin’,” and “Some Kind of Magic.” On the flip side, four songs that made my skin crawl and that I strongly dislike were: “Somebody That I Used to Know,” “Rumor Has It,” “Sweet Dreams Are Made of This,” and “Look What You Made Me Do." In my ears, there's something very abrasive and "noisy" about the last four songs that sounds like nails on a chalkboard in my ears. But, I can't put my finger on what trait these songs have in common.

Based on your research of timbre and other qualities of music that influence how listeners respond to certain popular music, do the eight aforementioned songs that I "love" and "strongly dislike" represent any common listener patterns you've observed in your MuSci lab?

ZW: One of the advantages of having participants select their own music to use in a study like this is that we were able to focus in on the situational, subjective elements of musical taste. Some people love classical, others heavy metal or Top 40 pop—the range of preferences out there are wide, and this aspect of the design allowed us to capture part of what makes music special (or annoying) to each individual participant. In our small sample people overwhelmingly selected rock, rap, pop, and electronic dance music (as opposed to classical, jazz, etc.) as their “liked” pieces, and genres such as heavy metal and country as their “disliked.” In interviews with participants before the scan, a common refrain was that metal was considered noisy, aggressive, and made people feel uncomfortable, while country was considered socially suspect irrespective of the actual sound (too conservative, “redneck,” etc.—remember, these were undergraduates in Los Angeles).

Aspects of what you found make some sense to me. The Adele is certainly a bluesy, rough-hewn number with slightly overdriven guitar, pounding, resonant drums, and some vocal mic overdrive (around 1:40 in particular); I can see how you might find aspects of its performance and production “noisy.” (Given your affection for Madonna, however, the ‘80s synth-pop of the Eurythmics makes less sense to me.) The Old Dominion and Josh Ritter examples are interesting from a social perspective. They are clearly marked as “country” in diction, vocal twang, idioms (“y’all”), etc. These are some of the more polarizing sounds in popular music today. Perhaps your affinity for them demonstrates empathy for the social groups often associated with country. Of course, this is all so situational and personal that it’s impossible to really say: I guess this demonstrates just how complex and socially determined the construct of musical taste really is!

CB: Lastly, as a published composer, bassist, performer of the Japanese shakuhachi flute, and expert on how the timbre of music influences music listeners: Do you have any specific music samples you can share with Psychology Today readers that exemplify the music-empathy connection based on your life experience and/or findings from your laboratory experiments at SMU-UCLA?

ZW: When I was an undergraduate in New York from 1999 to 2003, I performed a lot of very “difficult” music—harsh and dissonant free jazz improvisation at tiny clubs and bars serving the city’s underground music aficionados (for example, music like John Zorn).

To me and many audience members, this kind of music was pure bliss: wild, vital, and uncompromising in its sincerity. I ate it up. But occasionally, a fellow musician would bring a friend along to these shows who had not yet been initiated into the world of free jazz. Their reaction was typically the polar opposite: it was “screeching,” “cacophony,” “dying animal music,” and so on. Often I noticed an implicit moral judgement in these evaluations of my beloved music as “nothing but noise,” a subtext that goes something like: This music isn’t good for you; it’s chaotic and unintelligible. How could someone like you like this trash? What does it say about you that you do? These experiences vividly illustrated to me the social entanglements of everyday music listening. In some cases, a collapse of empathy for music is akin to a breakdown in social or interpersonal understanding. This study, as well as others that SMU colleagues and I are currently working on, aim to help us better understand how music listening relates to how we process and structure our social world.

Zach — Huge thanks for the great conversation and for providing so much insight and food for thought. Much appreciated! Please keep us posted on your upcoming book from Oxford University Press.

References

Zachary Wallmark, Choi Deblieck, Marco Iacoboni. "Neurophysiological Effects of Trait Empathy in Music Listening." Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience (2018) DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00066