Teamwork

If You Help Others, They Will Be More Willing to Help You

Direct and indirect reciprocity make people more willing to help each other.

Posted May 13, 2021 Reviewed by Lybi Ma

Key points

- Cooperation has evolved as a successful strategy for many animal species and human societies.

- Until recently, evolutionary game theorists have struggled to create models that simulate why and when players cooperate or help others.

- A new unified framework of "direct reciprocity" and "indirect reciprocity" sheds light on the evolutionary emergence of cooperation.

"Money is not the only commodity that is fun to give. We can give time, we can give our expertise, we can give our love, or simply give a smile. What does that cost? The point is, none of us can ever run out of something worthwhile to give." —Steve Goodier, One Minute Can Change a Life (1999)

Imagine a small town with two notorious citizens. One is legendary for being the local equivalent of Ebenezer Scrooge; he's stingy, Machiavellian, and never lends a hand to help others in need. The other community member has a reputation for being more like Mahatma Gandhi; he lives by the motto: "The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service to others." He has a reputation for being philanthropic, generous, and always willing to help neighbors in need.

Now, imagine that both of these people find themselves in a crisis that requires cooperation—which person do you think local townspeople would be more inclined to help first?

Based on a new evolutionary game theory study (Schmid et al., 2021) into the emergence of cooperation, one could speculate that townspeople would be more willing to help their altruistic neighbor for two reasons. First, he's directly helped lots of people in the past (i.e., direct reciprocity). Second, he has a glowing reputation for being a magnanimous do-gooder (i.e., indirect reciprocity).

This two-pronged "unified framework of direct and indirect reciprocity" was recently created by Laura Schmid and colleagues at Austria's Institute of Science and Technology (IST) and published on May 13 in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Human Behaviour.

The Evolution of Cooperation: Direct and Indirect Reciprocity Are Key

For this study, Krishnendu Chatterjee's computer-aided verification of game theory group at IST Austria created a new mathematical framework that quantifies how direct and indirect reciprocity affect cooperation.

The researchers found that the most selfish players were ultimately less likely to flourish and survive during the game. Instead, the perks of direct and indirect reciprocity made cooperation and teamwork a more successful strategy than selfishness.

The researchers designed a game that allowed players to be helpful and cooperative with others. Their computer-aided simulations made it possible to predict how prior exchanges and each player's reputation affected people's willingness to cooperate with a specific individual. "Using an equilibrium analysis, we characterize under which conditions either of the two strategies can maintain cooperation," the authors write.

"Using mathematical tools that were developed only recently, we explored which strategies of direct or indirect reciprocity give rise to a Nash equilibrium," Schmid said in a news release. "Once the evolving population of players in our simulation adopts such strategies, none of them has an incentive to divert."

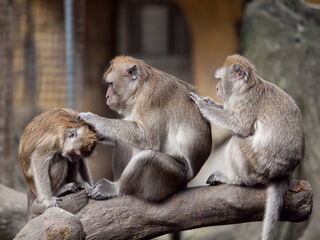

Direct Reciprocity Is Common Among Humans and Other Species

Direct reciprocity means that individuals (or animals) decide whether or not to cooperate based on direct personal experience and the tit-for-tat nature of giving to get something in return during an exchange.

"An interaction based on direct reciprocity simply means: 'I'll scratch your back if you scratch mine,'" Laura Schmid explains. "[Direct reciprocity] can be found both among humans and several animal species."

Indirect reciprocity means that even if someone hasn't been helped directly via a one-on-one exchange, for example, if onlookers know someone has a good reputation and solid track record of helping others, they'll be more willing to cooperate and offer help. Indirect reciprocity is primarily based on an individual's reputation. Having a good reputation creates a type of halo effect that makes people more willing to help someone who's helped others.

Indirect Reciprocity May Be Uniquely Human

Schmid et al.'s new unified model of direct and indirect reciprocity has the potential to advance our understanding of some fundamental dynamics underlying how cooperative strategies have evolved and stabilized among modern-day humans. According to Schmid, "So far, [indirect reciprocity] has conclusively only been shown among humans."

"These findings shed some light on how the evolution of cooperation in early human societies could have been influenced by their social norms based on experience and reputation," the authors conclude.

In future research, Laura Schmid plans to investigate the effect that direct and indirect reciprocity has on "the spread of social norms within a society" and "how many players in a group have to use a strategy based on indirect reciprocity for it to become successful."

References

Laura Schmid, Krishnendu Chatterjee, Christian Hilbe & Martin A. Nowak. "A Unified Framework of Direct and Indirect Reciprocity." Nature Human Behaviour (First published: May 13, 2021) DOI: 10.1038/s41562-021-01114-8N