Body-Focused Repetitive Behaviors

What Is Psychodermatology?

Exploring the intricate relationship of mind and skin.

Updated March 10, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

Key points

- Some people have an irresistible urge to pick at their skin or pull out their hair.

- These body-focused repetitive behaviors are broadly categorized as obsessive-compulsive disorders.

- They are often underreported, and those who suffer may fail to seek treatment out of embarrassment and shame.

- The behaviors can be focused and intentional or develop automatically as a way of self-soothing

“When I heard this, I tore my tunic and cloak, pulled hair from my head and beard and sat down appalled…then, at the evening sacrifice, I rose from my self-abasement,” wrote Ezra, a scribe and priest of biblical fame (Ezra 9.1-13). The Israelites, forsaking holy commands, were intermarrying their sons and daughters with people from a “land polluted by corruption,” and Ezra, distraught by their sins, felt “too ashamed and disgraced” to lift his face to God.

Early references to hair-pulling due to psychological distress include Aristotle, who wrote of the “morbid state” of those who pluck out their hair and gnaw at their nails (Nicomachean Ethics), and Hippocrates, who described a woman with periodic fevers who plucked and picked at her hair (Epidemics III.)

“Tearing our hair out,” with examples from Homer to Shakespeare (Kim, 2014; Waas and Yesudian, 2018), is a common expression of frustration, exasperation, grief, or even madness that has persisted throughout the centuries.

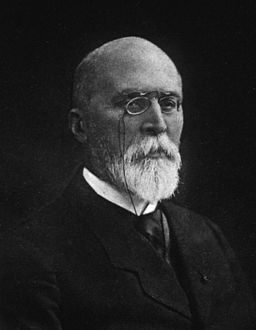

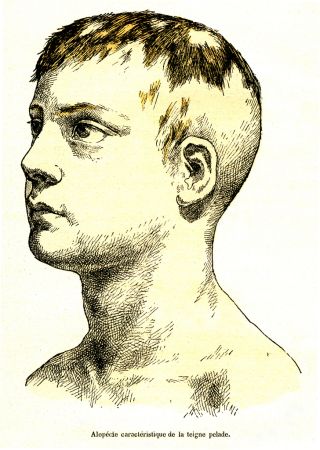

There are those, however, who suffer from a compulsive urge to pull out their hair. It was 19th-century French dermatologist François Henri Hallopeau who first coined the term trichotillomania (Altmeyer, 2023; Hallopeau, 1899.) Hallopeau described a young man who developed alopecia per grattage—alopecia from scratching. His patient pulled out clumps of hair from his entire body, including his head, beard, pubic hair, eyebrows, and eyelashes, creating “artificially-induced” alopecia.

Trichotillomania, characterized by recurrent, irresistible hair-pulling, is a “psychiatric disorder with dermatologic consequences” (Ghani et al, 2024). It is part of the relatively new multidisciplinary field of psychodermatology “that explores the intricate interplay between the mind and the skin” and aims to remove the stigma and shame often inherent in the symptoms.

The prevalence of psychiatric disorders with dermatological symptoms presenting to dermatologists is estimated to be up to 30% to 40% (Turk et al, 2022).

Trichotillomania is one of the disorders, including skin picking, cheek chewing, and nail-biting, described under the “umbrella term” of body-focused repetitive behaviors (Christensen and Jafferany, 2024; Grant et al., 2024; Okumus and Akdemir, 2023).

Though there is a continuum in severity, these disorders may lead to significant physical damage (e.g., baldness, infection, severe skin excoriations) and psychosocial impairment (Odlaug and Grant, 2008). The prevalence “of clinically meaningful” body-focused repetitive behaviors varies between 0.5% and 4.4% (Okumus and Akdemir), but it may be considerably higher due to underreporting and failure to seek treatment (Malayala et al., 2021; Parsa et al., 2023).

Most, but not all studies, (Grant et al, 2023), indicate these behaviors are far more common in women (Odlaug and Grant). Trichotillomania often begins in adolescence (Odlaug and Grant) but can appear during childhood (Torales et al, 2021). Hair plucking most commonly occurs on the scalp, but like Hallopeau’s patient, it can involve any body part (Krishnan et al., 1985). The pattern of hair loss can be described as “bizarre with irregular borders” or even like a “Friar Tuck” appearance (França et al, 2019). There is often a genetic component, with family members experiencing symptoms, most commonly nail-biting (Grant et al, 2023).

Skin picking, also called excoriation disorder or dermatillomania (Malayala et al.), has a bimodal pattern. It usually begins in the early 20s or between 30 and 45 years old (Odlaug and Grant). Without treatment, these behaviors tend to be chronic in most people (Grant et al., 2023).

Picking and plucking can be an automatic habit, without intention or awareness, or focused, with intention due to prior thoughts, sensations, or emotions (Parsa et al). Those who are focused hair pullers may explain that their hair feels different or odd (França et al), and those focused on skin picking may describe skin that appears uneven or discolored (Malayala et al).

Those without conscious awareness may have developed the habit as a form of self-soothing (Chamberlain et al, 2007) that became “functionally autonomous over time” (Parsa et al). Some patients have both picking and plucking symptoms, and those with concomitant symptoms can spend hours a day engaging in these repetitive behaviors (Odlaug and Grant).

When signs do present, and a patient does not acknowledge the behavior, a clinician must rule out other etiologies, including underlying diseases such as atopic dermatitis, thyroid or liver disorders, or those due to medications or vitamin deficiencies (Parsa et al.)

A pattern of hair loss, described as moth-eaten alopecia, for example, originally characteristic of secondary syphilis, may result from other causes, including alopecia areata (Sharquie and Ahmed, 2021), an autoimmune disorder that causes non-scarring hair loss (Goldberg, 2023; Englander et al, 2023). Sometimes, clinicians must perform a biopsy for a diagnosis (Torales et al).

About 20% of those with trichotillomania will eat their hair (Grant and Chamberlain, 2016). There are rare cases in which patients with severe psychiatric illness present with abdominal pain from gastrointestinal obstruction due to a trichobezoar, a foreign body formed of undigested hair. When the tail of the hair extends from the stomach to the small intestine, it is referred to as the Rapunzel Syndrome (Moolamannil et al, 2023; Poirier et al, 2024).

Several theories account for the symptoms, including the stimulus regulation model, which indicates that hair, skin, and nails are quite sensitive and pleasantly rewarding to touch. Further, they may reflect the evolutionary role of grooming, whereby grooming has served the functions of hygiene, thermoregulation, social interaction, and stress regulation (Okumus and Akdemir).

Another theory implicates emotion regulation: the behaviors decrease unwanted negative emotions (Crowe et al, 2024), including boredom, disappointment, and unhappiness “as a result of a mismatch between unrealistic expectations and personal standards” (Okumus and Akdemir).

In earlier versions of our Psychiatric Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM III), trichotillomania and skin picking were categorized as impulse disorders, but by DSM 5, they are considered obsessive-compulsive disorders. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and even substance abuse may exist concomitantly, as well as other obsessive-compulsive rituals such as checking in the mirror or even taking photos of the areas (Torales et al; Grant et al, 2023).

Various behavior modification techniques, including habit reversal therapy (Grant and Chamberlain) can help. These included behavioral contracts, self-monitoring, relaxation training, collecting hairs in an envelope, modifying the environment to reduce cues (Grant and Chamberlain), and even electrical aversive conditioning (Krishnan et al).

Along those lines, microneedling has been used as an adjunctive treatment for trichotillomania. This technique involves intentionally creating a wound that stimulates release factors involved in wound healing. Its effectiveness may result from the fact that it not only stimulates hair growth but reproduces the sensation of hair pulling (Christensen et al., 2022).

Clinicians have also tried various supplements and medications, including a glutamate modulator, such as N-acetylcysteine (Christensen and Jafferany), dopamine receptor blockers, such as olanzapine and aripiprazole (Okumus and Akdemir), opiate antagonists, such as naltrexone (Ghani et al), and anti-depressants, such as clomipramine or the SSRIs, all with limited success. There are no clear medication guidelines, and pharmacotherapy is often paired with behavioral modification.

Note: Special thanks to Ms. Arlene Shaner, Historical Collections Librarian at the New York Academy of Medicine, and Mr. Kevin Pain, Library Research Specialist at the Samuel J. Wood Library of Weill Cornell Medicine, for their assistance in retrieving references not readily accessible.

References

Altmeyer P. (2023). François Henri Hallopeau. (Health Sciences Library System): http://www/altmeyers/org/en/dermatology/hallopeau-francois-henri (Retrieved 2/29/24)

Aristotle (350 BC). Nicomachian Ethics, Book VII, chapter 5. (Translated by W.D. Ross) http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/nicomachaen.7.vii.html (Retrieved 3/6/24)

Bible. Book of Ezra 9.1-13 (New International Version):

https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Ezra%209&version=NIV (Retrieved 3/6/24).

Chamberlain SR et al (2007). Lifting the veil on trichotillomania. American Journal of Psychiatry 164(4): 568-574.

Christensen RE; Jafferany M. (2024). Unmet needs in psychodermatology: a narrative review. CNS Drugs 38: 193-204.

Christensen RE et al (2022). Microneedling as an adjunctive treatment for trichotillomania. (letter) Dermatologic Therapy 35: e15824. (2 pages)

Crowe E et al (2024). The association between trichotillomania symptoms and emotion regulation difficulties: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 346: 88-99.

Englander H et al (2023). Alopecia areata: a review of the genetic variants and immunodeficiency disorders associated with alopecia areata. Skin Appendage Disorders 9(5): 325-332.

França K et al (2019). Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder): clinical characteristics, psychosocial aspects, treatment approaches, and ethical considerations. Dermatologic Therapy 32(4): p.e.12622 (9 pages).

Ghani H et al (2024). From tugs to treatments: a systematic review on pharmacological interventions for trichotillomania. Clinical and Experimental Dermatology: llae052. Online ahead of print. (35 pages.)

Goldberg LJ. (2023). Alopecia—new building blocks. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 89(2S): S1-S2.

Grant JE and Chamberlain SR (2016). Trichotillomania. American Journal of Psychiatry 173(9): 868-874.

Grant JE et al (2023). Clinical characteristics of trichotillomania. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 35(4): 228-233.

Grant JE et al (2024). Disorders of impulsivity in trichotillomania and skin picking disorder. Journal of Psychiatric Research 170: 42-46.

Hallopeau FH. (1899): Alopecie par grattage (trichomanie ou trichotillomanie). Annales Dermatologie et Syphiligraphie 10: 440-441.

Hippocrates, (1962). Volume I: Epidemics Book III, Case XV. Edited by T.E. Page et al; Translated by W.H.S. Jones. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, Loeb Classical Library. pp. 283-285.

Kim WB. (2014). On trichotillomania and its hairy history. JAMA Dermatology 150(11): 1179.

Krishnan KR et al (1985). Trichotillomania—a review. Comprehensive Psychiatry 26(2): 123-128.

Malayala SV et al. (2021). Dermatillomania: a case report and literature review. Cureus 13(1): e12932 (5 pages.)

Moolamannil MC et al (2023). Two cases of Rapunzel syndrome in adult males. Journal of Surgical Case Reports 10: rjad571.

Odlaug BL; Grant JE. (2008). Trichotillomania and pathological skin picking: clinical comparison with an examination of comorbidity. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 20(2): 57-63.

Okumus HG; Akdemir D. (2023). Body focused repetitive behavior disorders: behavioral models and neurobiological mechanisms. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 34(1): 50-59.

Parsa L et al (2023). “Pick” wisely: an approach to diagnosis and management of pathological skin picking. Clinics in Dermatology 41(1): 41-48.

Poirier A et al (2024). A case of Rapunzel syndrome. Journal of Visceral Surgery 161(1): 72-73.

Sharquie KE; Ahmed A-AA. (2021). Moth eaten alopecia as a manifestation of group of skin diseases: reporting a series of 100 cases. Journal of Clinical Images and Medical Case Reports, Volume 2 (5 pages).

Torales J et al (2021). Hair-pulling disorder (trichotillomania): etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment in a nutshell. Dermatologic Therapy 34(1): e13466 (8 pages.

Turk T. et al (2022). The global prevalence of primary psychodermatologic disorders: a systematic review. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 36(12): 2267-2278.

Waas RLV; Yesudian PD. (2018). Plucking, picking, and pulling: the hair-raising history of trichotillomania. International Journal of Trichology 10(60: 289-90.