Education

The Science Behind Learning From Other People’s Advice

A new study reveals that people see non-human sources as less reliable

Posted March 15, 2023 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- Every day, we make decisions to follow other people’s advice or advice from other, non-human sources.

- Even the suggestion that the source of a piece of advice is human can change how we process the information.

- New research suggests that other people are viewed as more reliable sources.

- Specific parts of the brain respond to advice from other people compared to non-social advice.

This post was written by Nadescha Trudel, Ph.D., with edits from Patricia Lockwood, Ph.D., and Jo Cutler, Ph.D.

Every day, we need to make decisions about what advice to trust.

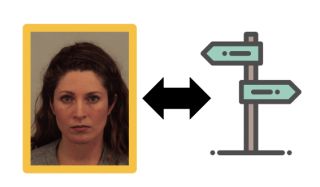

Should I listen to a colleague about what directions to take to a new building, or should I look for road signs to navigate the correct path? We know that humans' decisions are influenced by their beliefs, which may be based on advice from other people or, alternatively, on information from non-human sources, such as road signs. But which sources do we find more reliable, and do our brains respond differently when following social or non-social advice? Previous research investigated whether people will follow social advice, but it was unknown whether people processed information differently when coming from social sources and whether the type of information source has an effect on our confidence in how good the advice is.

A new study by myself and my colleagues investigated the differences in how people evaluate information from human sources who provided them with advice, compared to sources that were simply non-human inanimate objects. We also monitored brain activity while people made these decisions. In the process, we revealed new insights into how people form beliefs about social advice—such as the advice's reliability—and also discovered what happened in their brains.

A new experiment to measure social advice

In our study, participants completed tasks in which they could earn a small amount of money for finding a hidden dot. In one version of the experiment, people needed to locate the hidden dot on a circle after they received a clue on the dot's location from an image of a human face (social advice), whom they were told was a human advisor. In another version of the task, they also received a clue to the dot location, but this time the clue was provided by an inanimate object (non-social advice).

Designing the study in this way allowed our team of researchers to use the latest advances in data science to test how people processed the different types of advice. Another important factor in the study was that we could measure learning. People received the information repeatedly from many different advisors and inanimate objects, and they had to learn over time which of the two sources was more or less reliable. We also asked participants to report on how reliable they thought the advice was each time they decided. Crucially, we also measured what was happening in people's brains whilst they made these decisions.

People find social advice more reliable than non-social advice.

Looking at how people performed on the task, my colleagues and I found that participants were more certain when making judgments about the accuracy of cues given by human advisors compared to inanimate objects. They also updated their assessment of human sources less when new evidence contradicted their initial belief. This suggests that people may form more stable opinions about the reliability of information from humans, possibly because they expect other people to be more consistent in their behavior. When judgments were made about an inanimate object, they were based more strongly on recent experiences with that object than on past experiences.

The results of measuring people's brain responses showed differences when learning from the two advice sources. We found that parts of the brain known as the temporoparietal junction and dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, which had previously been linked to interacting with other people in studies by independent researchers, tracked how stable judgments were about the advisors. This suggests that the brain responds differently when learning advice from social compared to non-social sources.

These findings fit with recent work suggesting that although people learn from both social and non-social information in a way that is similar in terms of the learning process, there might be particular parts of the brain that are relatively attuned to processing social information. Having these brain areas sensitive to social information could be very important in understanding disorders related to social cognition, such as psychopathy. Future studies could test how people with high levels of psychopathic traits respond to learning from social versus non-social information. Some studies suggest that those high in psychopathy might indeed show differences, particularly in social learning.

More broadly, our work shows that even the suggestion that a piece of advice is from a human can change how people process the information. This is especially important because humans spend increasingly more time in the digital world. Awareness of our biased assessment of human sources will have implications for designing interactive tools to guide human decision-making as well as strategies to develop critical thinking.

References

Behrens, T. E., Hunt, L. T., Woolrich, M. W., & Rushworth, M. F. (2008). Associative learning of social value. Nature, 456(7219), 245-249.

Brazil, I. A., Hunt, L. T., Bulten, B. H., Kessels, R. P., De Bruijn, E. R., & Mars, R. B. (2013). Psychopathy-related traits and the use of reward and social information: a computational approach. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 952.

Konovalov, A., Hu, J., & Ruff, C. C. (2018). Neurocomputational approaches to social behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 24, 41-47.

Lockwood, P. L., Apps, M. A., & Chang, S. W. (2020). Is there a ‘social’brain? Implementations and algorithms. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 24(10), 802-813.

Pauli, R., & Lockwood, P. L. (2022). The computational psychiatry of antisocial behaviour and psychopathy. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 104995.

Trudel, N., Lockwood, P. L., Rushworth, M. F., & Wittmann, M. K. (2023). Neural activity tracking identity and confidence in social information. Elife, 12, e71315.