Memory

Using "Creative Forgetting" to Address Unwanted Memories

Creative forgetting may help you deal with the memory of an unpleasant experience.

Posted February 12, 2024 Reviewed by Monica Vilhauer

Key points

- Most of us have problematic personal experiences that we would love to forget.

- Our survey on how people modify their memories reveals strategies to address troubling recollections.

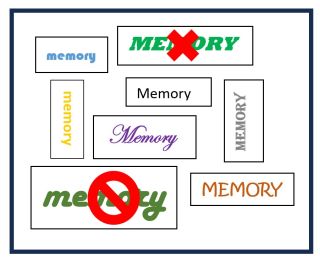

- Focused forgetting involves blocking, interference, eliminating reminders, depersonalizing, erecting barriers.

The night after my high school graduation, most of my classmates hit the bars to get drunk. Rather than join them, I picked a tamer celebration, assuming that I would be less likely to get into trouble. I grabbed some laundry detergent and emptied the box into an outdoor fountain near the school. After admiring my sudsy celebration for a while, I decided to return home and call it a night. I soon discovered that someone else had been there silently observing my festivities.

Immediately after I walked into my house and saw my parents’ faces, I regretted not getting drunk. I’ll skip the details, but rest assured that both the humiliation and punishment seemed appropriate. In the following weeks, I wished that there was a way to remove this embarrassing experience from my memory. I couldn’t figure out how, so I quietly endured the unpleasantness until I went off to college. If I had only known then what I do now (read on).

Survey of Creative Forgetting Techniques

In an earlier blog post on autobiographical editing, I discussed how many of us try to modify memories of our personal past to make a better, more coherent or more interesting story. This may involve such things as adding or cutting particular details, as well as merging similar events together. Included in the autobiographical editing questionnaire in Brown et al. (2020) was a speculative question on whether people ever attempt to completely expunge unwanted recollections. That is, when a life episode is too unpleasant to dress up, do we ever try to get rid of it?

In answer to this question (“Have you ever tried to intentionally eliminate your own memory of an unpleasant experience?”) about half (51%) of respondents said that they had; this was more common among the college students (59%) than in the community (33%) sample. While some research exists on how trauma survivors wrestle with their memories of terrible events, there appears to be none on ad hoc strategies used among a broader sample of people to eliminate their recollections of less intense unpleasant experiences. We were quite surprised not only at how many people had tried this focused form of creative forgetting, but also at how many of these (81%) were also willing to describe their strategies. They include:

- active blocking – interfering with their own memory access by repeating over and over “That did not happen!” or “I don’t remember that.”

- setting up interference – engaging in competing mental activities (homework) or physical chores (laundry) whenever the unwanted memory pops to mind, hopefully weakening the strength of the recollection.

- eliminating physical reminders – discarding memory triggers, such as selfies, clothing, gifts, phone numbers or social media connections.

- depersonalizing – reframing the memory as if it were a TV show episode or had happened in a dream.

- erecting passive mental barriers – placing a lock on the “mental drawer” that contains the memory; erecting roadway barricades (police tape, hazard cones, flashing warning lights) barring access down the path leading to that memory.

These creative forgetting strategies connect to research with trauma survivors, in that some of Epstein and Bottom’s (2011) subjects cited avoidance and relabeling to explain the temporary forgetting of their harrowing experiences. However, that research emerged from a different orientation (repressed memories) with small sample sizes and a limited range of experiences (traumas). Our study, in contrast, casts a wider net with a larger and more representative sample of individuals, and a broader possible range of negative memories. Forgetting techniques have also been studied in the lab (including directed, targeted and intentional forgetting, as well as retrieval suppression and interference), but this research mostly involves neutral materials (i.e., word lists) rather than personal experiences.

Clearly, there are limitations with the present research. These data are based on self-reports, and individuals were not required to describe the specific memory that they attempted to discard (in order to respect their privacy). However, both “limitations” may actually have resulted in underestimating the incidence of creative forgetting. More specifically, it seems likely that at least some persons in our survey may not have wanted to admit to unpleasant personal experiences that they had tried to eliminate.

Conclusions

To summarize, we found that many people employ a variety of creative forgetting strategies to intentionally address unwanted memories. While we are all taught in school how to learn, were any of us given lessons on how to forget? If so, I missed that day! But seriously, it is impressive how many people apparently devise and apply such techniques on their own and are willing to share what they do. Realistically, it is unlikely that we can completely erase all of our bad memories by such techniques. But it is reasonable to expect that creative forgetting can reduce the impact, accessibility or intrusiveness of such recollections.

It is important to emphasize that these findings are preliminary, and many more questions remain: Where do people pick up these mental skills? What specific types of memories do they attempt to eradicate? How successful are they in eliminating or reducing the recollections? In efforts to understand how our memory functions, it is important to know how individuals manage recollections of their own experiences. Mining such information gained from our everyday functioning can be essential in forming laboratory approaches to refine our understanding of real-world experiences. Such an approach has proved valuable with such phenomena as the tip of the tongue (Schwartz & Brown, 2014) and déjà vu (Cleary & Brown, 2022) experiences. Similarly, knowledge about what people devise on their own to address unwanted recollections can also be translated into laboratory research to evaluate the efficacy of each approach.

As a final thought, perhaps a systematic application of creative forgetting techniques has potential for improving mental health. Wouldn’t this tool be useful for therapists in helping patients deal with persistently unpleasant recollections? Some steps have already been taken in this direction (Hertel & Mathews, 2011). Such an approach would not replace traditional therapy but could help reduce or remove the troubling impact of specific events. Maybe such techniques would have benefitted me decades ago to rinse away the graduation night unpleasantness from my personal memory bank and keep it from bubbling back up into my conscious awareness.

References

Brown, A. S. (2018). May I borrow your life? On second thought, I’ll edit my own. Presidential Address presented at the Southern Society for Philosophy and Psychology, San Antonio, TX.

Brown, A. S., Fields, L. M., Croft Caderao, K., Chmielewski, M., Denman, D., &Marsh, E. J. (2020). Autobiographical editing: Rewriting our personal past. In B. L. Schwartz & A. M. Cleary (Eds.), Quirks of memory: The study of odd phenomena in memory. NY: Routledge.

Cleary, A. M., & Brown, A. S. (2021). The déjà vu experience (2nd edition). New York, NY: Routledge.

Schwartz, B. W., & Brown, A. S. (2014). Tip of the tongue states and related phenomena. Cambridge University Press.