Attention

Blindsight: When Your Eyes See More Than You Realize

Sometimes, we may see and react to stimuli we are not consciously attending to.

Updated March 11, 2024 Reviewed by Davia Sills

Key points

- A person's visual system may be designed to process information to which they may not be paying attention.

- Stroke patients with “blind” areas in the visual cortex can still detect features of stimuli projected there.

- Regularly sighted people may similarly be designed to detect and react to unconscious visual stimuli.

I played racquetball for many years with a good friend and colleague, Mike. We hit the courts early in the morning so that we could finish in time to teach our 9:00 a.m. classes. Mike was a gifted athlete, lettering in multiple sports in both high school and college. His raw athletic ability far exceeded mine, but one of his moves on the court consistently baffled me.

Near the end of our session, he would saunter to the back of the court, glance at the wall clock, and declare how much time we had left to play. This part of his game made no sense to me for several reasons. First, the analog clock on the gym wall was 70 feet away. But more importantly, my nearsighted colleague never wore his glasses when we played because he could easily track the ball’s rapid movements without them. Maybe Mike could see that there was a clock there, but certainly not the hands on its face.

What is Blindsight?

He invariably moved us along to make our classes on time, so I was grateful for his uninterpretable skill. When I finally pushed him about it, he gave me a brief lecture on blindsight and the seminal research by Larry Weiskrantz (1990). This phenomenon is found in patients with stroke damage to portions of the primary visual reception area of the brain. These individuals are unable to detect the presence of objects projected to that damaged location. Despite this, Weiskrantz found that they were still able to verify some of the object’s features, such as its direction of movement, size, or orientation.

How does this relate to our racquetball game? Mike explained that like the blindsight patients, even though he couldn’t actually “see” the clock hands, he could surmise their position. This still sounded a bit fishy, and I suggested that he just might be a lucky guesser. Undeterred, he issued a challenge in a form that we both understood—an experiment!

The Blindsight Experiment

Rather than use individuals with stroke damage, we recruited 23 legally blind university students, defined as having 20/200 uncorrected vision (or worse). We sat them in front of a computer, without their glasses, and used an analog clock face containing just an hour hand and no numbers.

Their task was simple—tell us which hour the hand was pointing to after seeing the clock face flash on the screen for one second. We used a number of trials with different hour positions and tested subjects both with and without their glasses on.

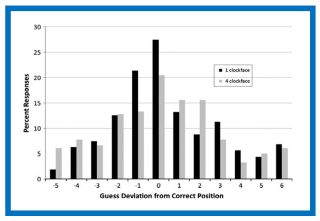

The results were quite impressive! Some information about the time was being detected in their “blind” (no glasses) condition, despite protests from the subjects that they could see nothing but a blurry circle briefly appear on the monitor. The hour was correctly guessed 28 percent of the time, which was well above chance (8 percent) (Brown et al., 2013). Furthermore, when guesses were wrong, they declined in a systematic manner away from the correct position.

We made the task even more challenging, and the subjects again surprised us. They were now shown four different clockfaces flashed simultaneously on the screen, but only one contained an hour hand and the other three were blank.

Although their accuracy (21 percent) was a bit lower than with one clock face condition—as expected with this more difficult task—it was still significantly above chance (8 percent). Again, as in the single-face condition, they often protested that they could not see anything and felt like they were just responding randomly. After being assured that they were still doing just fine, they became more comfortable with their “guesses” (or, at least, what they thought were guesses).

So, my racquetball partner won the bet. But how does this finding relate to how we deal with the world around us? At a general level, it suggests that we all may be able to detect features of objects even when we don’t think that we can.

How Blindsight May Apply to Us All

While this broad speculation may be difficult to directly test with normal-sighted individuals, here are some possible everyday examples. Have you accidentally bumped a glass on the dinner table with your elbow or clumsily knocked a beer bottle at the bar with your hand? Most likely, you immediately grab for the object before realizing what you are doing. If lucky, you momentarily marvel at your catching reflex which felt as if it originated from some mysterious operating system. If you weren’t so lucky, you were aghast at your clumsiness.

We suggest (Brown et al., 2013) that your lucky grab is guided by the same system underlying blindsight in visually impaired stroke patients. That is, a secondary visual track involving the parietal lobe plays a role in many visual experiences. This may help blindsight patients identify stimulus location, orientation, or direction of movement in the same way that it guided my colleague’s—and our research subjects’—ability to identify the hour-hand position without the sensation of “seeing” it.

Speculatively, this secondary visual track may occasionally help you avoid serious harm.

How about that time when you jumped out of the path of a passing car at the last moment, the one that you didn’t notice because you were absorbed in a phone conversation? I’m confident that this mechanism once saved me. I was sitting right behind the dugout at a professional baseball game. When the batter at home plate swung and missed, his bat slipped out of his grip. I was looking away, talking to a friend next to me, as the bat flew directly at my head. I ducked just as the man sitting one row in front of me caught the bat with one hand! I’m convinced that an automatic reaction related to blindsight helped protect me from serious harm.

Conclusions

So, if you were successful in saving that fancy wine glass from shattering at the dinner party, count yourself fortunate to be assisted by a brain system operating just beyond your full awareness but still assisting you in processing important details. Unfortunately, one of my friends was not served so well by this. Rather than a valuable wine glass, he successfully caught a small potted prickly cactus midair as it tumbled off his work desk—and got the scratches to prove it.

References

Brown, A. S., Best, M. R., & Mitchell, D. B. (2013). More than meets the eye: Implicit perception in legally blind individuals. Consciousness and Cognition, 22, 996-1002.