Sensory Processing Disorder

It’s Not Autism, It’s Sensory Processing Disorder

The two conditions are often confused, but they’re not the same.

Updated April 20, 2024 Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Many people on the autism spectrum have atypical responses to certain sensations. One person might become overwhelmed in a noisy, brightly-lit shopping center, while another might have to cut all the labels out of their clothing because they can’t stand the feeling of the tags rubbing against their skin.

Those sensory sensitivities were believed to be hallmarks of autism for decades, until new research began to reveal that sensory processing disorder (SPD) may be a condition all its own.

SPD presents in one of three broad patterns:

- Sensory modulation disorder, which impairs a person’s ability to regulate their response to sensations. Someone with this pattern of SPD might overreact to, under-react to, or excessively crave sensory input.

- Sensory-based motor disorder, in which problems with the sense of balance or the sense of body position make it challenging for a person to plan and execute movements.

- Sensory discrimination disorder, which causes difficulties in interpreting sensations. A person with this type of SPD might have trouble telling the difference between the letter N and the letter M or might not be able to tell when they have to use the bathroom.

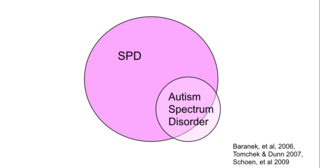

SPD was conflated with autism spectrum disorder for many years because SPD is so common in autistic individuals. Recent studies suggest that between 90% and 95% of people on the autism spectrum have sensory processing differences.

The reverse, however, doesn’t hold true: Most people with SPD aren’t on the autism spectrum. While about 1 in 45 adults and 1 in 54 children in the United States are autistic, as many as 1 in 6 children may have SPD significant enough to affect their everyday lives.

Further evidence that SPD and autism are distinct conditions came out of the University of California, San Francisco, where a study showed that there are differences in brain structure between boys with SPD, autistic boys, and neurotypical boys.

“One of the most striking new findings is that the children with SPD show even greater brain disconnection than the kids with a full autism diagnosis in some sensory-based tracts,” said Elysa Marco, the study’s corresponding author. “However, the children with autism, but not those with SPD, showed impairment in brain connections essential to the processing of facial emotion and memory.”

There is a debate in the medical community as to whether SPD should be recognized as a separate diagnosis or whether sensory dysfunctions are simply a set of symptoms that crop up in a variety of other conditions like autism, ADHD, and anxiety disorder.

For individuals or for parents of children with SPD, though, the difference is somewhat academic. From a practical perspective, if you (or your child) are affected primarily by sensory dysfunction, then it’s important to distinguish that disorder from other conditions so that you can receive appropriate treatment.

To learn more, visit the Sensory Therapies And Research Institute.