Fear

Tachysensia Is Another Name for Alice in Wonderland Syndrome

Could tachysensia and Alice in Wonderland Syndrome spells be migraine symptoms?

Posted December 6, 2020

Good news!

After collecting detailed accounts of tachysensia episodes from readers of my November 13, 2020 post, “The Tachysensia Population Is Larger Than We Thought,” I was able to link every one of them to clinical reports going as far back as the middle of the last century.

On behalf of the large community of fast-feelers on Reddit and my Psychology Today blog, I talked with several expert neurologists and psychiatrists who have particular interests in matters of short-lived perceptual distortions. Now, with that professional confirmation, knowing that tachysensia and Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS) — both characterized by perceptual distortions, not by hallucinations or illusions — share symptoms common to those experienced in migraineurs, I am glad to say….

Hold on. First, a disclaimer: I have no proven clinical expertise in neuroscience. My accounts come from researched journal information, conversations with neurologists and psychiatrists, and my readers’ descriptions of their experiences. Some symptoms resulting from tachysensia/AIWS might require clinical attention. If you have any concerns about your condition, you should first speak to your physician, then, if necessary, consult a neurologist.

With that understanding, what I can say now is that symptoms of tachysensia/AIWS —feelings of zoomed motion, time, and body — are mostly collective symptoms connected to migraines. Testimony for this goes back to the mid-twentieth century when top neurologists were studying AIWS patients. That brings good news to the many people concerned about their rare but frightening spells.

The symptoms

Symptoms of any human condition are tricky to categorize. The complexity of the human body machine necessitates an understanding of body function disparities. Two different people can have identical syndromes related to two distinct etiologies, so we must consider distinctions in arguing a cause. We know what causes a migraine, but we do not know precisely why symptoms vary so prominently between migraineurs. One might have episodes limited to headaches, another to light flashes, another to loud voices, another to distorted perceptions. And for some, the sensations could be all of many of the above.

Symptoms of any medical condition come in a wide variety of sensations, often an assemblage of many. That’s why we have labels on our prescribed medications: May cause drowsiness. May cause dizziness. May, not will.

The cause of migraines is better known now than it was a half-century ago. The belief is that its symptoms are the result of fluctuations in necessary electrochemical communications causing shifting waves of vasoconstrictions of blood vessels, a control system there to regulate and maintain arterial blood pressure. Therefore, I am pulled to the thought that migraines—though often appallingly painful—might be beneficial to the body’s health.

The migraine

Although a migraine can set off a tachysensia/AIWS episode, understanding how it happens is not fully understood. The neurologists I spoke with affirm that a migraineur’s apparent distortion of the size of objects and their spatial relation comes from some electro/vascular singularity.[i] The migraine itself sets off a shifting wave of electrical charge distribution between the nerve cells in the cerebral cortex.

This shift of electrical activity brings on a release of potassium and calcium ions, which, in turn, activate nociceptor neurons, sensory receptors pain stimuli charged to warn of any portending credible attacks to a part of the body. That activation relays signals, through sensory pathways, to the thalamus (a center for pain perception) and then onto the sensory cortex. Since nociceptor neurons are part of the peripheral nervous system, along the way — particularly along the sensory pathways — signals could become confused in regulating perceptions of pain, temperature, touch, sound, time, and visual discernment. That is when distortions in body images and speed become apparent to the migraineur.

Peculiar clinical cases that describe an altered sense of vision, hearing, and time had been noted ever since the early nineteenth century as neurological syndromes. It took a fifty-year stream of new cases for the condition to elevate to naming status. We call it Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS), a disorienting condition that gives one the perception that they have grown immensely large or exceedingly small.

Neurologists still have little understanding of the pathophysiology of AIWS, even though more and more cases are appearing under the concern of a few conditions, such as migraines, epilepsy, some viral infections, and intoxicant medications. But here is what I do know—fleeting and infrequent symptoms generally do not point to neurological illness; persistent, frequent symptoms, though, could raise the likelihood.

It is very likely that the four names used to describe similar feelings—Tachysensia, Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, Todd’s Syndrome, and Rushes—are simply titles for remarkably similar symptomatic experiences related to migraines, but not quite.

I believe that most tachysensia/AIWS experiences are symptoms directly related to migraines. But I am reminded of nine case histories dating back to 1989 (too few to judge a cause) of patients under the care of neurologists at the Isaak Walton Killam Children’s Hospital in Halifax, Nova Scotia. They experienced distorted perceptions of time and space, symptoms associated with a disease once called “The Rushes.”

Symptoms differed from patient to patient. One case was that of a 13-year-old boy who had nine episodes of perceiving everything in his surroundings as moving exceedingly fast. Each lasted just five minutes. No headaches. The sounds were loud. Rough objects felt smooth. He was conscious and able to speak normally, though he seemed to compensate for his assumed rapid speech by speaking slow. An EEG, taken during one of his attacks, was normal.

Another was that of a 14-year-old girl who “felt that everything in her surroundings moved too quickly.” Objects in the room seemed either too large or too small. In her case, the headaches came soon after her strange feelings. Her EEG was also normal.[iii] Other children at the same hospital heard loud voices along with their fast-feeling episodes.

For many years Dr. Caro Lippman, a physician and early investigator of Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, asked his migraine patients if they had any unusual body sensations just before the onset, or during, or just after of their headaches. In 1952 he wrote the following in The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease.

“Those patients who have these [perceptual distortions] worry about themselves, fearing that they are on a road to insanity. They actually confess to me that they have never told another doctor about their experiences because of fear of being thought ‘crazy.’ As soon as they are reassured that their sensations are not unique, and after they are allowed to chat with other migraine patients who have had similar [perceptual distortions], they cease to be afraid, and view their experiences with a sense of mild amusements.”

The insertion “perceptual distortions” is mine. It replaces Lippman’s use of “hallucinations.” I believe he was using the word “hallucinations” under its mid-twentieth century broadest understanding. But wow! That must have been good news back then.

I am knowledgeably supported by neurologists and psychiatrists when I repeatedly say that whatever one feels while under a tachysensia /AIWS spell is likely just one of those rare hiccups that prove we are living beings. Do not fear them, as long as they are brief and infrequent, as long as they do not seriously debilitate the ability to carry out the daily task of living successfully, and as long as your episodes do not build in intensity. It’s best to take them as wondrous interludes to tell others. They are short-circuited moments that throw off the electrochemical “memory” of how time should pass. If you have few and far between spells of that strange phenomenon called tachysensia or Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, celebrate your few natural moments of speed and body sense. They are glorious reminders of being human.

The survey

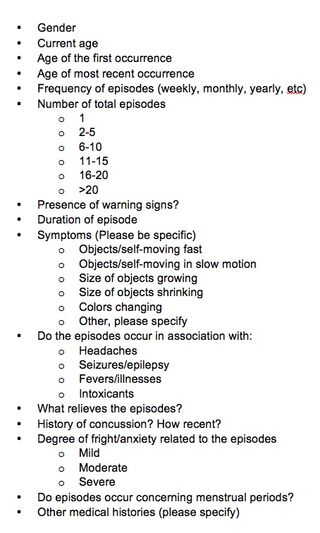

That said, there are still things to be done. I will be working with Dr. Osman Farooq, Clinical Associate Professor of Neurology at the SUNY Buffalo Jacobs School of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, to gather data and foundational material for neurologists who will investigate tachysensia/AIWS. We hope to validate what we believe to be the cause of tachysensia/AIWS symptoms. With enough case accounts provided by you, dear reader, we shall come to a more thorough understanding of this fascinating experience. Please help us by filling out the bulleted survey on the left and sending it to tachysensia@gmail.com. Anything sent will be kept confidential.

A name change proposal

The word syndrome attached to AIWS might be correct by definition; after all, what is a syndrome other than a group of symptoms that characterize a particular medical condition. Unfortunately, the word portends a frightening disorder. So, I propose here that we change the name to Alice in Wonderland Experience (AWE) and that that experience includes the fast feeling symptoms of tachysensia. After all, even the Red Queen in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass tells us, “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

There will be more to come on this fascinating subject that we should from now on call AWE. Stay tuned.

© 2020 Joseph Mazur

References

Osman Farooq MD, Edward J. Fine MD, “Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: A Historical and Medical Review,” Pediatric Neurology, 77 (2017) 5-11.

Joseph Dooley, Kevin Gordon and Peter Camfield “The Rushes: A Migrain Variant With Hallucinations of Time,” Clinical Pediatrics (Sept. 1, 1990) Vol. 29 No. 9 536-538.

Gerald S. Golden, "The Alice in Wonderland Syndrome in Juvenile Migraine" Pediatrics, (April 1979) 63 (4) 517-519.

Lippman, C. W. (1952). "Certain hallucinations peculiar to migraine," Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 116, 110-116.

Gowers WR. The Border-land of Epilepsy, Faints, Vagal Attacks, Vertigo, Migraine, Sleep Symptoms and Their Treatment, London: J. & A. Churchill; 1907. I-IV + 1-121.