Cognition

The Four Realms Versus the Four Planes of Existence

Comparing and contrasting two explorations of what it means to be human.

Posted June 7, 2024 Reviewed by Kaja Perina

What does it mean to be human? In The Four Realms of Existence: A New Theory of Being Human1, fellow PT Blogger, Professor Joseph LeDoux shares his perspective. It is a point of view guided by decades of research into the key elements that breathe life into our existence. The core of his argument is that we can understand ourselves as being constituted by ensembles of activity across four different layers of complexification.

LeDoux’s first realm is the biological layer. In three chapters, he explores the secrets of life and its key requirements, including metabolism and replication. He then turns to the bodies of organisms and shares an insight from Alfred Romer that divides the bodies of animals into visceral and somatic categories. The former includes digestive and metabolic processes that, in essence, align animals with plants, and thus can be considered “vegetative” in nature. The latter have to do with bones and muscles, setting the stage for coordinating movement.

Second, there is the neurobiological realm. He examines nerve cells and nervous systems and finally the brains of animals like bees and octopi. It ends with an analysis of “behavioral thoroughfare,” which LeDoux frames in terms of (noncognitive) reflexes, instinctual action patterns, and habits.

The cognitive realm is third. In six chapters, he explains what he means by cognition, how and why cognition emerges from the neurobiological layer, what are mental models and why the cognitive realm is about internal mental models, and why only birds and mammals are cognitive creatures.

Finally, there is consciousness. LeDoux importantly differentiates “creature consciousness” from “mental state consciousness.” The former refers to the way organisms exhibit functional awareness and responsivity. The latter refers to the subjective capacity to experience the world, which is his primary focus here.

Each realm is nested in the realm before (see here). Thus, consciousness emerges from cognition, which emerges from the neurobiological realm which emerges from the biological realm. LeDoux’s explains why he is a fan of higher order theories, and proposes his own, called the “multistate hierarchical theory of consciousness.”

LeDoux sees memory as central to consciousness and thinks the prefrontal cortex is crucial in accessing and integrating it. He professes to being uncertain about which other higher animals might have conscious mental states, and he advocates for a skeptical stance when doing science. His position is significantly more conservative about animal consciousness than the recently released New York Declaration on Animal Consciousness, which I endorse.

At the end of the book, he comes to human language. As a student, he worked under Michael Gazzaniga, who became famous for his work with split brain patients and developed the intriguing idea that the human ego functioned as an interpreter. LeDoux generally endorses this idea, and the final chapter is on the stories we tell ourselves and others.

Comparing LeDoux's Realms with UTOK's Four Planes

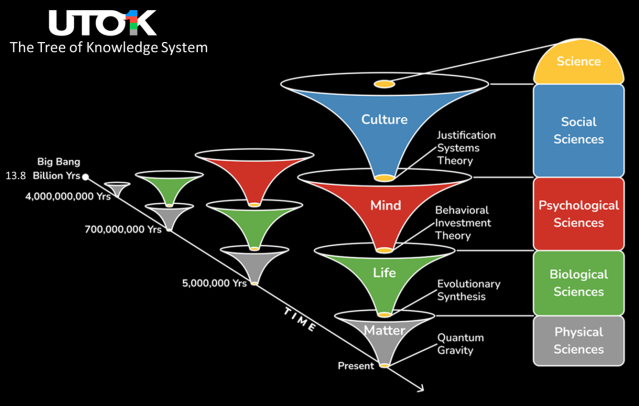

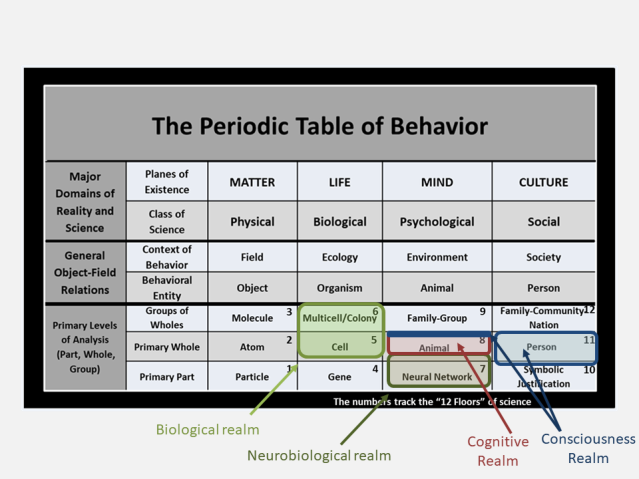

I enjoyed the book and several elements helped advance my thinking. Those familiar with UTOK, the Unified Theory of Knowledge2, will be able to see significant overlap, along with some important differences. To see both, we can enlist UTOK’s Tree of Knowledge System3 and Periodic Table of Behavior4 (PTB).

In looking at the ToK System, we see a major difference. It emphasizes four planes of existence (i.e., Matter-Object; Life-Organism; Mind-Animal; and Culture Person); however, they do not directly align with LeDoux’s realms. Moving “from the bottom” the ToK explicitly frames the Matter-Object layer as emerging out of the more fundamental Energy-Information Implicate Order. Other than claiming that “everything is physical,” LeDoux does not provide much in the way of clarifying these issues.

A more significant point of difference, however, pertains to the Culture-Person plane of existence (in blue) that exists above the Mind-Animal plane (in red). LeDoux is missing the joint point between Mind-Animal and Culture-Person, which means he is missing a crucial distinction between the self-conscious Egoic narrator and the conscious primate Self (see here). This argument has been in the literature since 20035, so it is a shame that it was overlooked.

If we shift to the Periodic Table of Behavior, which provides a more detailed analysis of the ontological layers in nature, we can trace where LeDoux’s four realms fit in the UTOK frame. Specifically, floors 5 and 6 on the PTB correspond to LeDoux’s biological layer. Floor 7 on the PTB aligns with the neurobiological layer, and would align with animals like sponges and jellyfish.

Floor 8 on the PTB refers to “minded animals” (see here). A minded animal is an animal with a brain and complex active body. This can also be called the domain of “neurocognitive activity,” which can be then divided into the neurocognitive information processing that takes place within the brain, and the overt actions of animals as they behave6. Creatures like bees and octopi, and many others, are (neuro)cognitive creatures. Because of the way he defines cognition, however, LeDoux places these animals into the neurobiological camp. This is why I show the neurobiological domain stretching into the bottom of Floor 8.

"Higher" minded animals, like birds and mammals, align with LeDoux's cognitive realm. As suggested above, UTOK has a broader definition of cognitive (see here). Language is tricky and this difference in terminology does not mean that we are seeing the world completely differently. Indeed, via Behavioral Investment Theory, UTOK makes a division that is very similar to the division that LeDoux makes. Specifically, it divides minded animals into three broad categories7: (1) reactive, consisting mostly of reflexes and instinctual motor patterns; (2) learning animals that adjust their behavior to consequences and develop novel habits; and (3) thinking animals that can generate internal working models and simulate possible outcomes. The category of “thinking animals” aligns with the cognitive realm, defined as internal mental models.

Things get fuzzier when we get to consciousness. For LeDoux, consciousness is a highly complex network that generates subjective experience that can be accessed and is tied together via memory and attention. For now, we can label this “higher order, animal-into-human consciousness.” I think a strong argument can be made, however, that flashes of mental state conscious experiences (e.g., instances of pleasure and pain) emerge much earlier in the evolution of animal mindedness.

I also disagree with LeDoux regarding the “top end” of consciousness, specifically how to frame language-based, human self-consciousness. As noted, UTOK draws a clear line with the emergence of propositional language, which generates the self-conscious human Ego (which is different from the conscious primate Self) and the Culture-Person plane of existence8. This latter dynamic is completely missing from LeDoux’s analysis. You can see on the PTB that there is a blue line on top of animals into the domain of persons.

The problem here is that the analysis lacks a frame for how we develop as socialized persons. Yes, LeDoux points to the story telling self; however, it is lumped in with the realm of primate consciousness and provides no clarity regarding the context in which we tell stories, or how and why this evolved. The analysis misses Justification Systems Theory9 and the Culture-Person plane. It is a blind spot that, if filled in, could have enhanced the work (e.g., see here for how JUST connects to the interpreter function).

In sum, The Four Realms is an interesting read, that offers some valuable insights about the layered ensemble stretching from biology to neurobiology to cognition to consciousness. I think its richness could be strengthened substantially if it was placed in the larger, more coherent UTOK framework for understanding what it means to be a human person.

References

1. LeDoux, J. E. (2023). The four realms of existence: A new theory of being human. Harvard.

2. Henriques, G. (2022). A new synthesis for solving the problem of psychology: Addressing the Enlightenment Gap. Palgrave MacMillan.

3. Henriques, G. R. (2022). The Tree of Knowledge System. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 119-152). Palgrave Macmillan.

4. Henriques, G. R. (2022). The Periodic Table of Behavior: Mapping the levels and dimensions in nature. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 253-284). Palgrave Macmillan.

5. Henriques, G. R. (2003). The tree of knowledge system and the theoretical unification of psychology. Review of General Psychology, 7, 150-182.

6. Henriques, G. R. (2022). Mental behaviors and the Map of Mind1,2,3. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 287-319). Palgrave Macmillan.

7. Henriques, G. R. (2022). A metatheory of Mind1. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 321-355). Palgrave Macmillan.

8. Henriques, G. R. (2022). Mind3 and the Culture-Person plane of existence. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 427-464). Palgrave Macmillan.

9. Henriques, G. R. (2022). Justification Systems Theory. In A New Synthesis for Solving the Problem of Psychology (pp. 87-118). Palgrave Macmillan.