Free Will

An Attack on Free Will

Why luck often trumps pluck.

Posted October 17, 2023 Reviewed by Abigail Fagan

A review of Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will. By Robert M. Sapolsky. Penguin Press. 528 pp. $32.

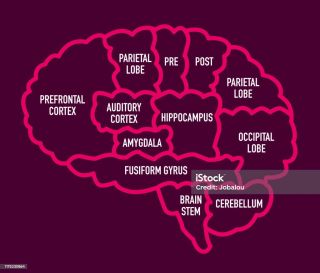

Free will, Robert Sapolsky (professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University, recipient of a MacArthur Foundation Genius Grant, and the author, among other books, of Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst) reminds us, is usually defined as the ability of the brain to spontaneously generate and consider alternative options, select one, and decide whether to act on it.

Sapolsky considers this claim akin to believing that human beings possess a non-biological essence “bespangled with fairy dust.”

In Determined, Sapolsky maintains that all beliefs, values, and behavior (“the way you became you”) result from the complex, uniquely individualized interactions of genes, brain chemistry, fetal, infant, and childhood nurture, and the social and cultural environment, over which human beings have no control. Thus, while we can will what they choose (open a door, pull a trigger), we cannot choose what we choose. And just as it makes no sense to blame a tornado for destroying your house, no one deserves to be treated better or worse than anyone else.

Recognizing that he will not convince all, most, or many of his readers that “there is no free will whatsoever,” Sapolsky indicates that he will settle for getting some of them “to reframe their thinking about both everyday lives and our most consequential moments,” especially about how to deal with crime and punishment and whether dethroning free will encourages bad behavior.

In my judgment, he has succeeded in this aim. Witty and engaging, Determined is also a goldmine of fascinating information (most of it accessible even to those of us who aren’t scientifically literate) about neuroscience; philosophy; chaos theory; emergent complexity; quantum indeterminacy; evolving knowledge of the causes of epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism; and, of course, the impact of nature and nurture on decision-making.

A study “that should floor anyone holding out for free will,” Sapolsky writes, concluded that for each step up in The Adverse Childhood Experiences (abuse, neglect, household dysfunction) score, the likelihood of adult antisocial behavior, including early pregnancy, substance abuse, poor cognition, depression, and violence, increased by about 35%. Differences between rainforest and desert dwellers, rice growers and wheat farmers centuries and millennia ago, Sapolsky reveals, continue to have an impact. Defendants appearing before a judge who has just had a meal have a 65% chance of parole; hours later that chance is dramatically lower. Far from providing evidence of free will, Sapolsky demonstrates, chaos theory is about the virtual impossibility of predicting outcomes, but silent on the issue of determinism. And if behavior is rooted in quantum indeterminacy, it must be random.

At times, Sapolsky seems needlessly provocative. The decision to forego a party to study, drop out of school, or steal something, he writes, is “as purely biological” as flinging your leg out when you’re struck on a certain spot on your knee, only to add that all but the reflex response are affected by interactions with the environment.

More important, Sapolsky realizes the importance of reconciling “an absence of free will with the fact that change occurs.” He points out that Norway’s “open prison” system, with rooms instead of cells, furnished with computers and TV, dramatically reduces the rate of recidivism. In progressive societies, including the United States, attitudes toward gay marriage flip-flopped in a generation. And they are doing a better job of setting assessments of personal responsibility in the context of the circumstances into which each of us was born, live and work. It’s what football coach Barry Switzer meant when he quipped, “some people are born on third base and go through life thinking they hit a triple.” It’s what critics have in mind when they oppose legacy admissions to college and advocate affirmative action for underrepresented minorities.

Ending widespread belief in free will, then, may not be all that important. That is, if we add momentum to these trends, as Sapolsky recommends, by closing the gap between the economic, educational, and social circumstances of wealthy and poor people; understanding why luck often trumps pluck; and, wherever possible, praising and condemning, rewarding and punishing good and bad behaviors instead of judging the individuals who engage them.

Here’s hoping we find the will to usher in this more humane world.