Machiavellianism

The Dark Side of Political Ambition

Machiavellian personalities may enjoy political campaigning more than others.

Posted December 6, 2019 Reviewed by Devon Frye

In personality psychology, Machiavellianism refers to a cynical and manipulative approach to interpersonal relationships that embraces “moral flexibility” for personal gain. People high in Machiavellian traits, or “Machs,” place a high priority on money, power, and competition, and are said to pursue their goals at the expense of, or at least without regard for the welfare of, others (Jones & Paulhus, 2009).

Machiavellianism has also been identified as a member of the “dark triad,” a group of socially aversive, self-centered traits that also includes narcissism (a grandiose sense of one’s own superiority to others and feelings of entitlement to special treatment) and psychopathy (callous disregard for the rights of others combined with reckless impulsivity) (Jones & Figueredo, 2013).

Although all three members of the dark triad share a common core of interpersonal antagonism, there has been debate about to what degree they are distinct from each other. In particular, there have been concerns that existing measures of Machiavellianism essentially tap the same traits as psychopathy, and therefore may be redundant (Miller, Hyatt, Maples‐Keller, Carter, & Lynam, 2017). However, a recent study (Peterson & Palmer, 2019) suggests that Machs are notable for their political ambition, whereas psychopaths do not care much for politics. Hence, there may be a meaningful and theoretically relevant distinction between Machiavellianism and psychopathy after all.

Although the concepts of Machiavellianism and psychopathy share common elements, such as willingness to use manipulation and deceit to achieve one’s goals, psychopathy is also associated with impulsivity, whereas, in theory, Machs should be more planful and oriented to long-term rather than short-term goals. Additionally, it has been suggested that, unlike psychopathy, Machiavellianism is associated with less violent, less overtly aggressive forms of misconduct, such as cheating, lying, and betrayal, especially when retaliation is unlikely or impossible (Jones & Paulhus, 2009). For example, Machs are more likely to cheat on term papers than multi-choice tests. Hence, their cheating tends to be strategic, rather than recklessly impulsive.

On the other hand, some research suggests that, contrary to theoretical expectations, current measures of Machiavellianism are associated with impulsivity and excitement-seeking. Additionally, although all members of the dark triad are associated with low agreeableness (a personality trait reflecting concern for the well-being of others), in theory, Machiavellianism, unlike psychopathy, should theoretically be associated with high conscientiousness, a trait associated with impulse control and long-term planning.

However, a review of studies (Miller et al., 2017) found that both psychopathy and Machiavellianism are associated with low conscientiousness instead, suggesting that both Machs and psychopaths are likely to be poor at long-term planning and thinking before they act. To be fair though, the same review found that psychopathy had significant positive associations with conduct problems including antisocial behavior, substance abuse, and gambling, whereas Machiavellianism did not. This is somewhat in line with the view that Machs are more likely than psychopaths to be selective and strategic in their behavior rather than taking impulsive risks in general.

Despite this, the authors argue that current research using existing measures of Machiavellianism is really measuring psychopathy, and that better measures of Machiavellianism that capture the ability to engage in long-term planning while also tapping the selfish, manipulative nature of the concept are therefore needed.

Despite the apparent shortcomings of existing measures, there is evidence that shows interesting differences between Machs and psychopaths that are relevant to the theoretical core of Machiavellianism. A study (Peterson & Palmer, 2019) on the dark triad and political ambition found that there were differences between each of the three dark traits in how they were related to specific interest in specific activities relating to working in politics. Specifically, they found that both narcissism and Machiavellianism were related to interest in running for office and feeling qualified to be in power, whereas psychopathy was not. Furthermore, Machiavellianism alone was related to having a positive view of specific activities related to activities involved in running for elected office, including fundraising, working with party officials, interacting with the press, and taking the time needed to run for office. Narcissism was unrelated to interest in any of these activities, whereas psychopathy was related to an active dislike of all of these activities.

This indicated that although narcissists liked the idea of running for office, they had little interest in doing the actual work involved. Machs, on the other hand, seemed to think that they would enjoy the day-to-day business of campaigning for office, whereas psychopaths found the idea unappealing.

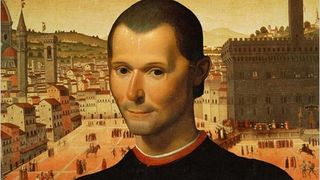

Hence, this seems to suggest that Machs and psychopaths differ sharply in their attitudes to behaviors required to gain political power. The authors suggest that psychopaths might lack a desire to interact with others, whereas Machs might actually enjoy the process of interacting with people for the purpose of influencing them politically. This would also be consistent to some extent with Machs being more interested in long-term planning and having a desire to gain power than psychopaths. Considering that the word Machiavellianism is named after the political philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli, this finding seems particularly fitting.

A limitation of the political ambition study was that it only used self-report measures and did not assess any objective outcomes, so it is not clear if Machs objectively do better in politics than psychopaths or narcissists. However, another study in Germany using objective measures of career success found that Machiavellianism was positively associated with obtaining a leadership position in a company whereas psychopathy had a negative association (Spurk, Keller, & Hirschi, 2016). That is, Machs were more likely to obtain positions of responsibility at work than psychopaths—which would suggest that despite the similarities between them, there are at least some theoretically expected differences between outcomes associated with Machiavellianism and psychopathy, even when using currently existing measures.

This seems to suggest that, despite their apparent impulsivity and low conscientiousness, Machs are willing and able to take a hands-on approach to achieving their ambitions, whereas psychopaths do not seem to care, perhaps because they do not have driving ambitions or do not enjoy doing the dirty work of politics.

Additionally, previous research (Jones & Paulhus, 2009) suggests that Machs thrive in unstructured organizations in which they have latitude for improvisation and are subject to fewer rules and restrictions, and in which they have opportunities for face-to-face interaction, perhaps so they can practice manipulating people. In this respect, it may actually be fitting that measures of Machiavellianism are associated with low conscientiousness. People who are high in conscientiousness tend to be orderly, like following rules and may appreciate highly structured working arrangements. On the other hand, Machs may perform poorly in overly structured working environments, so their low conscientiousness may go hand-in-hand with their preference for flexibility and improvisation. Perhaps Machs enjoy political campaigning because it allows them to be flexible and affords opportunities for improvisation.

For these reasons, it seems that Machiavellianism may still have a distinctive place in the dark triad and may be important in understanding the nature of political ambition.

References

Jones, D. N., & Figueredo, A. J. (2013). The Core of Darkness: Uncovering the Heart of the Dark Triad. European Journal of Personality, 27(6), 521–531. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1893

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior. Guilford Press.

Miller, J. D., Hyatt, C. S., Maples‐Keller, J. L., Carter, N. T., & Lynam, D. R. (2017). Psychopathy and Machiavellianism: A Distinction Without a Difference? Journal of Personality, 85(4), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12251

Peterson, R. D., & Palmer, C. L. (2019). The Dark Triad and nascent political ambition. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 0(0), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2019.1660354

Spurk, D., Keller, A. C., & Hirschi, A. (2016). Do Bad Guys Get Ahead or Fall Behind? Relationships of the Dark Triad of Personality with Objective and Subjective Career Success. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550615609735