Placebo

The Power of Expectation

How the placebo effect can help you train in the gym.

Posted May 30, 2023 Reviewed by Michelle Quirk

Key points

- What we expect to happen can shape what actually does happen.

- Expectations can be about something beneficial or something bad.

- Researchers studied of the effects of expectations on the effectiveness of exercise training.

Most people know, or think they know, what a placebo is. A placebo is a “medicine” that isn’t really a medicine yet acts in the same way as a real medication does. Placebos have an effect because the person taking them believes and expects that they will have that effect.

The flip side of placebos is nocebos (from the Latin for “I shall harm”). The nocebo effect happens when a person taking a placebo expects that there will be negative effects to that medication. If you tell someone that a placebo will treat whatever the problem is; however, it will also produce a headache, the odds that the patient will report a headache go up. The power of expectation, for both a positive and negative outcome, is tremendous.

The question of just how and why placebos work is still unresolved. Most of the research has focused on the use of placebos to treat pain. Pain is subjective, meaning it is experienced differently by different people. Different expectations produce different pain before treatment even begins. Pharmaceutical treatment of chronic pain has potentially very dangerous side effects like addiction, tolerance, and the potential for overdose. So, harnessing one’s own mind to help in the task of managing pain has enormous appeal.

Using functional magnetic resonance imaging, neuroscience researchers have discovered that placebos and nocebos work in the brain by activating pain modulation pathways in the brainstem, the same pain modulations pathways that are activated by real pain and real analgesia (Crawford et al., 2021).

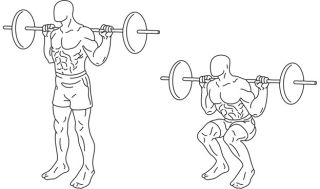

Placebos in the Gym

In an effort to examine interventions that might produce the placebo effect but that do not require pharmaceuticals, a group of researchers in Norway designed a pilot study of the effects of expectations on the effectiveness of exercise training (Lindberg et al., 2023). One group of volunteer athletes was told that they were going to train using an individually designed program based on their own unique force-velocity profile, or they were told that they would be in the control group. A profile is developed for an athlete after a performance test that measures the force and velocity of their performance on a vertical jump test. A different, individual exercise program is then created to target deficiencies in force, or in velocity, or in both.

Both groups actually received the same training program; however, the placebo group was told that the program had been designed specifically for them, while the control group believed that the training program was generic and not specifically designed to optimize their performance.

Study Results

After 10 weeks of training, both groups were again assessed. The placebo group improved their performance over the control group in only one of the assessment exercises (the one-repetition back squat). There was also an increase in thigh muscle thickness for the placebo group compared to the control, which should be correlated with leg strength. However, no significant differences in sprint speed or leg-press power were seen.

The authors speculated that there may have been a tendency for the placebo group, the group that believed they were receiving a training program designed uniquely for them, to be more compliant with the training regimen than the participants in the control group, or to try harder, and to push their limits more than did the athletes in the control group because they expected more of themselves or believed that the experimenters expected more of them. Or perhaps the control group, believing their training regimen to be “generic” and in no way special, were suffering from the nocebo effect.

The authors concluded that this is, to the best of their ability to discern, the first study to suggest that the placebo effect might be at least a partial explanation for differences in exercise training interventions, and perhaps in sport performance.

References

Crawford, L.S., Mills, E.P., Hanson, T., Macey, P.M., Glarin, R., Macefield, V.G., Keay, K.A., and Henderson, L.A. (2021). Brainstem Mechanisms of pain modulation: A within subjects 7T fMRI study of placebo analgesic and nocebo hyperalgesic responses. The Journal of Neuroscience, 41(47):9794–9806.

Lindberg, K., Bjørnsen, T., Vårvik, F.T., Paulsen, G., Joensen, M., Kristoffersen, M., Sveen, O., Gundersen, H., Slettaløkken, G., Brankovic, R., and Solberg, P. (2023). The effects of being told you are in the intervention group on training results: a pilot study. Nature/Scientific Reports, 13, 1972: doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-29141-7