BDSM

What We Can Learn About Ourselves From BDSM

Links between shame, judgment, and our desired selves.

Posted August 21, 2023 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Emotional reasoning and confirmation bias make us resist information at odds with what we already believe.

- When we act or think in ways that clash with our "desired" self, we tend to judge ourself and others.

- Self-acceptance frees us to understand ourselves and paves the way for change.

"Martha was freaking out because I enjoy hurting people," Zach said. And so she should! you might think.

But Zach and Martha are BDSM practitioners, and Zach acted with consent. Does that change your mind about Zach? Would you let it?

What we do with challenging or new information tells us a lot about ourselves.

BDSM refers to the overlapping acronyms of bondage and discipline, dominance and submission, and sadism and masochism. BDSM "play" is generally defined as including sexual behaviors that involve some sort of power exchange between two or more partners and/or the use of pain (or sometimes pleasure) to elicit sexual pleasure (Williams, 2006).

While only a small percentage of people identify as BDSM proponents, by some estimates 60 percent of us have had sexual fantasies of coercion, control, pain, and submission And one in five have at some time explored activities that come under the umbrella of BDSM.

Given that many of us share the curiosity, why does the BDSM community remain so stigmatized?

We may doubt whether consent could be genuine—yet consent is absolutely central to mainstream BDSM. Open, detailed discussions about the intentions, hopes, and boundaries of the participants are usual before any activities, and dominant partners are often valued for their care and empathy. All parties give explicit prior consent which can be withdrawn at any time, and folks breaking the rules are usually shunned.

Psychologists no longer view Zach’s kind of "consensual sadism" as pathological. Instead, the prevailing view is that such kinks—extreme as they may seem to some—are an extension of normal human sexuality.

Another widespread belief—that those who enjoy BDSM must be psychologically damaged—does not hold up to scientific scrutiny either. Those who identify as consensual dominants or sadists (and the consensual masochists, and those who enjoy either role) tend to enjoy mental health that is at least as good as the population at large. Consensual sadists typically fall within normal population ranges for empathy, and the BDSM community as a whole seems to have better communication skills than average.

Of course, there are some damaging and damaged people in the BDSM world—as in any walk of life—and it's no surprise that some folks fail to manage their own safety and that of others. Conversely, there are folks who use BDSM as a safe, boundaried space to work through pre-existing issues related to power and powerlessness. The research would of course take all of this into account. But the assumption that it is inherently unhealthy to practice BDSM appears unwarranted.

You might find yourself thinking "This can’t be true!" When something "feels wrong," it can be hard to shift our opinions even when given evidence to the contrary. These "thinking errors" or "cognitive biases" are a normal part of human thinking: Psychologists know that we are not as logical as we like to think.

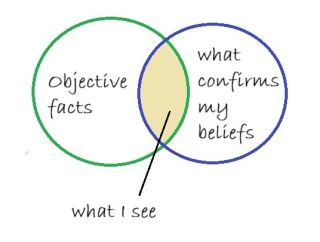

Emotional reasoning—"If I feel something, there must be good reasons to feel this way"—and confirmation bias—the tendency to focus on information that supports what I already believe—tend to lock us into our existing beliefs. But where do those gut feelings—and consequent judgments—come from in the first place?

Zach continued, ‘We had been doing things we’d discussed at length, that she’d wanted and consented to. Then one day she arrived raging, saying I was disgusting and should seek therapy." He seemed indignant and upset. "I told her she should go and explore her fantasies of control and pain with someone who shared her shame and guilt—which I don’t!"

Is Zach right that shame might be driving Martha’s sudden judgment of him? Quite possibly.

Despite Martha’s willingness to explore, she may be experiencing cognitive dissonance—the discomfort that arises when deeply held beliefs do not match our actions or other evidence. She may, for example, be struggling with enjoying things she "shouldn’t" like—or conversely, realizing she’s not as "open-minded" as she thought.

Incoherence between our actions and a desired self-image often leads to shame or guilt, depending on how self-accepting we are.

Via emotional reasoning, when these unwelcome feelings surface, they strengthen the belief that what we or others have done is inherently wrong. These harsh judgments of ourselves and others relieve our cognitive dissonance to some extent, as they strengthen one side of the argument in our heads. (It’s also a form of confirmation bias.)

Shame and judgment do go hand in hand—and our culture, especially when it comes to sexuality, is a shame-based one. When combined with complicated feelings about dominance and submission, pain and pleasure, we are prone to negatively judge ourselves and by extension others, in a subconscious attempt to relieve the immediate internal conflict.

Such defenses can stop us from ever addressing the underlying conflict, however. Compartmentalization, biased thinking, and self-judgment prevent us from seeing and accepting those conflicted thoughts enough to allow their exploration or resolution.

In this case, what are we to make of Zach’s apparent lack of guilt or shame? For some, our gut might tell us that that makes him a bad person. But it is self-acceptance that allows him to acknowledge and channel his desires openly, in a prosocial way. Is that bad?

Not all judgments are motivated by our own shame, of course. We may have come to rational reasons for not liking what we or someone else does, and we are perfectly entitled to say we "just don’t like something." However, we would be wise to remember that our most emotionally laden negative judgments are often driven by unresolved internal tensions and consequent judgments.

We do not need to explore BDSM to find self-acceptance. But we do need to find a nonjudgmental curiosity about what is in our heads. Can we aspire to enjoy our myriad, contradictory (possibly kinky) thoughts as they pass by?

And where do those beliefs about what we should be come from anyway? Parents? School bullies? Society? Can we work out who and what we want to be?

Self-acceptance is a compassionate understanding of where we are right now, but it’s not necessarily about accepting the status quo.

Facebook image: Goami/Shutterstock

References

Brown, A., Barker, E.D. & Rahman, Q. (2020) A Systematic Scoping Review of the Prevalence, Etiological, Psychological, and Interpersonal Factors Associated with BDSM, The Journal of Sex Research, 57:6, 781-811, DOI: 10.1080/00224499.2019.1665619

Hansen-Brown A.A., Jefferson S.E. Perceptions of and stigma toward BDSM practitioners. Curr Psychol. 2022 Apr 26:1-9. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03112-z. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35496362; PMCID: PMC9041285.