Parenting

Adolescents, Parents, and the Power of Reputation

How one is socially known can affect how one is treated.

Posted March 28, 2022 Reviewed by Devon Frye

Key points

- Reputation is a public impression of someone based on personal conduct and the opinion of others.

- Reputation is like a "shadow self" that precedes and follows everyone through life, sometimes to influential effect.

- During adolescence, reputation is partly created by social association with the peer group to which one belongs.

- While it's easy to depend one's parenting reputation on the performance of their adolescent, it can reduce pressure on everyone if they do not.

“I don’t care what others think of me!”

In proud defiance, the young adolescent may assert their independence from parental and public opinion to empower freedom to grow. There is the desire to be unrestrained by the eyes of the world, by social approval’s rule. But soon, standing with others starts to matter more. How one pleases peers can affect social belonging, while being on authority’s good side can ease one’s way.

This is a good time for parents to have the now vs. later conversation with their adolescent whose mind can often be on the present, not inclined to spend much time thinking ahead. They can talk about the power of personal reputation. And they can reflect on the felt importance of their own.

Reputation

So: What is reputation and how can it matter? Start by thinking about it in a general way. Reputation is how, through conduct and the opinion of others, a public impression of someone is created and conveyed by which that person is socially known. Like it or not, reputation attaches to people, both following and preceding everyone through their life, a public image of themselves that at times can stick. Reputation can be to the person’s advantage, and sometimes not.

Reputation is Powerful

Reputation can affect the course of a teenager’s life. For example, think of the last-stage adolescent (around ages 18-23) beginning to make their way in the world of work and applying for another job. Now a reference or recommendation provides positively valuable testimony to their reputation. In this way, reputation can practically affect occupational opportunity and mobility: “She was a slacker,” or “He was a hard worker.”

Parents can explain: “What your current employer thinks of you can materially matter when applying for your next position. So, even if you don’t like your current job, it can still be worthwhile to do it well.”

Reputation can affect school experience as well. For example: think of the early-stage adolescent (around ages 9-13) struggling through sixth grade. Reputation with a teacher can be educationally impactful because it can shape expectations that can make a difference in how one is initially treated. Thus, maybe a seventh-grade teacher was casually asking their sixth-grade counterpart about incoming students. What they are told about reputation might influence the receiving teacher’s expectation, shaping how a young person will be treated at first—maybe warmly if the image is positive (“She was a pleasure to have in class”), or watchfully if the image is negative (“Sometimes he could be a trouble-maker.”)

Parents can suggest: “How you act in one class can affect your reception in another.”

Realities of Reputation

Because reputation is so powerful, it can shape expectations which can affect the social response one receives. This is why parents can explain to their teenager some hard realities about reputation to say mindful of.

- “How you act affects how you are seen.”

- “The opinion of others shapes your reputation.”

- “Reputation now can impact how you are treated later.”

- “You can influence your reputation, but never actually control it.”

- “It’s hard to earn a good reputation, but harder to live a bad one down.”

- “Reputation is like a 'shadow self' that attaches to each of us in powerful ways. The actions you take can create the impression you make, which can affect the reputation you’re given, which can create expectations others set, which can influence the treatment they give, which can affect the experience you get. So, in relationship to others, it generally works in your favor to let your best side out.”

Beware

In this online age, while young people use social media to create, post, and promote themselves and the popular image they want to convey, they still cannot entirely control their reputation. And to make matters worse, sometimes peers use the Internet to "flame" (damage) another person’s reputation.

At worst, social vulnerability to media harassment can be created. Should this cause their teenager significant suffering, with the child’s permission, parents can intervene and electronically notify the perpetrators: “Know that you are now dealing with the parents of who you are attacking; and that if this behavior is not stopped immediately, we will directly contact your parents and other concerned powers-that-be.”

Reputation by Association

Then there is a thorny issue about reputation that resides at home.

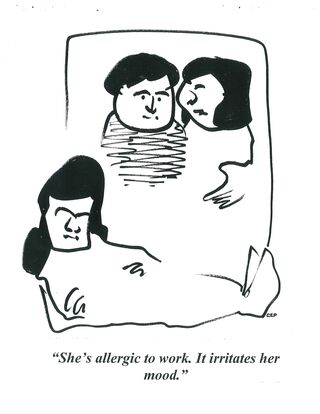

Everyone is partly known by the social company they keep. Run with a social crowd, an athletic crowd, or an alternative crowd, and you acquire some adolescent reputation by that association. “She’s one of them.” “He’s like his friends.” With peers, to some degree, “we” is “me.”

Then there is family.

Parent and child are by each other known, but parents tend to be more sensitive to how the child affects their reputation than the reverse. Consider why this might be so.

Parenting is a high investment relationship. Because moms and dads give a lot of themselves, they usually expect some significant return for all their efforts. “When we do our part, we expect you to do yours,” can be the operating assumption. To some degree, parents can treat their child’s well-being and conduct as a reflection of them, thus affecting their reputation. “We want you to behave well for you and for us.”

Because the adolescent is detaching from parents for more independence and differentiating for more individuality, growing changes create more contrast between them than existed when she or he was still a child. The old similarity connection between them has necessarily lessened. As the growing child now wants to be their own person, a changing definition can create a changing reputation.

The Reputation Equation

At this age, parents can be asked a casual question that can have a competitive impact: “How is your child doing?” Compared to what? Compared to whom? And now the reputation equation can be felt: parent = child. By implication, how the child does is a measure of parenting received.

In the extreme: If the child is performing well, that can affirm they are parenting well, and they may take some credit for the outcome of their efforts. “We must be doing something right!” However, if their child is struggling, they may assume some sense of blame, feeling partly at fault or even resentful because the child is making them look bad in the eyes of the world. “His troubles reflect poorly on us.”

But I believe, particularly when going through a wayward time with your teenager, it’s best to foreswear the reputation equation, thus reducing pressure on everyone—for pleasing and from disappointing. To separate responsibility, parents can simply declare: “What you do and how you do is ultimately about you; it is not about us. What is about us is our commitment to love you and guide you and stand by you the best we can.”

And when complimenting your adolescent on some positive performance, don't say "I'm proud of you," or "You make me proud," because both statements are self-congratulatory, like saying "You're doing well makes me look good!" Rather, keep the credit and reputation where it belongs by simply stating, "Good for you!"