Anger

How to Prevent Anger’s Damage to Your Brain

Anger was a survival trait, but now it has become destructive.

Posted December 14, 2023 Reviewed by Ray Parker

Key points

- Anger is an evolutionary neurological response.

- Anger often persists even though it no longer serves its original survival purpose.

- Replace anger with forgiveness; if that's not possible, try understanding.

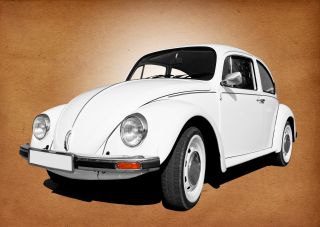

When I was in college and proudly showed my mother my new Volkswagen, she tearfully said, “How could you? The Germans murdered 33 of our relatives.”

I wanted to say, “Mom, the people who built my car weren’t born then; they aren’t responsible for the sins of their fathers.”

But her anger was so immediate and intense that I knew nothing would reduce her hostility toward anything German, from riding in a Volkswagen to eating schnitzel. I didn’t realize the neurological effects of her anger.

Anger and the Aggressive Amygdala

Anger is the brain’s reaction to events, ranging from my mother’s response to the horrific deaths of family members to a partner’s fury when not remembering a 25th wedding anniversary. This reaction, and others on the “offense” continuum, start in the amygdala, an almond-shaped bundle of neurons in the brain no bigger than a shelled peanut.

Five million years ago, the amygdala’s “fight or flight” response was essential for survival when velociraptors lurked in the forest, hoping our ancestors would be on the menu for lunch.[i]

You can think of the amygdala as a sentry that acts when it senses danger.[ii] If it snoozes, people die, or on a personal level, your ancestor becomes an appetizer.

Hardwired into the amygdala is the motto, “Better safe than sorry,” a reaction that caused our ancestors to flee at the sound of rustling in the forest rather than hoping to get close enough to pet the toothy monster lurking behind a tree.

Unfortunately, many of our hardwired traits linger thousands or even millions of years after their survival value has diminished.[iii] Anger appears to be one such trait.

Instead of anger becoming a little-used reaction with limited value, the amygdala remains on high alert, responding to words with the same ferociousness as if a passing insult was life-threatening rather than unskillful. This inappropriate reaction often results in unintended and hurtful consequences.[iv]

Anger’s Consequences

Tibetans have a saying, “You can throw hot coals at the enemy, but you’ll burn your hands in so doing.” The effects of anger have been well-documented, ranging from the destruction of interpersonal relationships to the impaired mental health of those who are consumed by it.[v] On balance, the survival value of anger does not seem to justify the damage it does to the initiator or the recipient of the emotion.

Your anger can rarely be contained, like spilled water on a countertop. Think about how your furious response affected interactions with everyone that day. An explanation of why you cannot isolate your anger about a specific event may come from neurological research.

Negative emotions—including anger—trigger other negative feelings that often result in depression or a prevailing sense of gloom.[vi] Think of a row of dominos where the tripping of one sets off a reaction that doesn’t stop until the last one falls.

Shakespeare got it right in The Merchant of Venice when Portia pleads for mercy.[vii]

The quality of mercy is not strained;

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest;

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

Mercy and forgiveness, precursors for bridling anger, can reduce or eliminate the damage the amygdala’s prehistoric reaction causes to both the thrower of hot coals and the person struck by them. But what happens when you can’t forgive? When an offense is so horrific that you believe even God could not forgive what the person did. The answer lies in understanding.

Try to Understand When You Can’t Forgive

Understanding is often mistaken for forgiveness. It is not. There are important distinctions between the two that involve both the heart and the head.[viii] I can’t forgive what the Nazis did to my relatives, but I can understand the dynamics that explain why they blindly followed a madman.[ix]

We routinely encounter situations in which a choice is necessary. We can become angry, forgive, or understand. Even when the response is justified, anger does nothing to render justice. Although forgiveness is healing, the greater the magnitude of the offense, the less likely it will occur. Sometimes, the only thing left is understanding.

Is understanding as comforting as forgiving? Absolutely not, but understanding won’t burn your hands as much.

References

[i] Kozlowska K, Walker P, McLean L, Carrive P. “Fear and the Defense Cascade: Clinical Implications and Management.” Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2015 Jul-Aug;23(4):263-87. doi: 10.1097/HRP.0000000000000065. PMID: 26062169; PMCID: PMC4495877.

[ii] Richard Y, Tazi N, Frydecka D, Hamid MS, Moustafa AA. “A systematic review of neural, cognitive, and clinical studies of anger and aggression.” Curr Psychol. 2022 Jun 8:1-13. doi: 10.1007/s12144-022-03143-6. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35693838; PMCID: PMC9174026.

[iii] Lahti, D. C., N. A. Johnson, et al. “Relaxed selection in the wild.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 2009; 24(9): 487-496 DOI: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.010

[iv] Williams R. “Anger as a Basic Emotion and Its Role in Personality Building and Pathological Growth: The Neuroscientific, Developmental and Clinical Perspectives.” Front Psychol. 2017 Nov 7;8:1950. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01950. PMID: 29163318; PMCID: PMC5681963.

[v] Richard, Y., Tazi, N., Frydecka, D. et al. “A systematic review of neural, cognitive, and clinical studies of anger and aggression.” Curr Psychol 42, 17174–17186 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03143-6

[vi] Kim, J., Andrews-Hanna, J.R., Eisenbarth, H. et al. “A dorsomedial prefrontal cortex-based dynamic functional connectivity model of rumination.” Nat Commun 14, 3540 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-39142-9

[vii] William Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice, (New York: Simon and Shuster, 2009)

[viii] Pettigrove, Glen. “Understanding, Excusing, Forgiving.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 74, no. 1, 2007, pp. 156–75. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40041031. Accessed 14 Dec. 2023.

[ix] Theodore Abel, Why Hitler Came Into Power, (Boston: Harvard University Press, 1986)